Coalmining in Slieveardagh

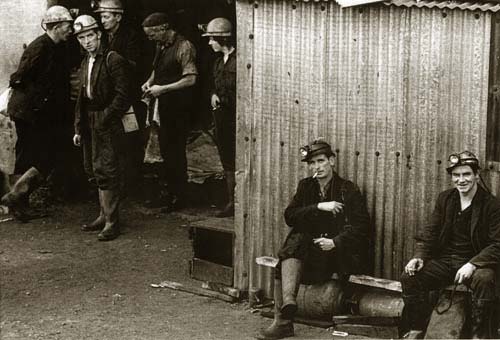

The coalfields of Slieveardagh are a continuum of the Carlow, Laois and Kilkenny coal vein. It is seldom if unique to find an industry which is passed on not only from generation to generation but spans more than three centuries. Aside from farming it has been the main source of income of the native people for close to four centuries, a feat which merits historical reference in itself.

During these bygone times the coalfields brought a measure of prosperity, employment and the promise of a secure future to many people. To the neighbouring towns of Killenaule, Thurles, Mullinahone, Callan, Urlingford and numerous other parts, the hard black anthracite, (known as ‘stone coal’ to many locals) brought work and a regular wage to thousands. Today many Irish people still associate Ballingarry with coalmining. However for the younger generation the controversy associated with the long and bitter ending of Ballingarry’s Coal Industry may unfortunately be why they recognise the name today. It’s history however makes interesting reading.

According to tradition, coal mining has taken place in this area for at least 400 years. It is recorded in the civil survey of 1654 that coal was being mined which was “suitable for blacksmiths at (cúl na choille) Coolquill. Indeed local folklore suggests the Danes mined the coal during their “visit” in the 9th century. Until 1825 the mines were worked almost exclusively by unlicensed private enterprise, Farmers large and small on whose land seam outcropping occurred. It is recorded that 35 mines were in production employing about 1000 men through the mid 1800’s.

Mardyke, known locally as ‘The Found’, is the first coalmining site in Slievardagh about which we have detailed information. The Mining Company of Ireland, established in 1824, began operations at Mardyke in 1825; by July 1826 an engine house and nine dwelling houses for workers had been erected. The first steam engine (14 horse power) in Slievardagh was introduced by Charles Langley for his colliery in Lisnamrock (Coalbrook). Mardyke village was launched in 1827 when the foundation stone, inscribed with the legend ‘industry, integrity and perseverance’, was inserted in a wall in front of the office/overseer’s house. A further 16 houses were constructed by 1832 and in 1848 Mardyke had a complement of 33 houses in three streets- New Street, Middle Street and High Street. I n 1841 there was a temperance hall, a saving’s society and a lending library in the settlement.

The Commons benefited from the development and growth of the Mining Company of Ireland. Five dwellings were built in the townland of Blackcommon. They were occupied by the families:- Owen Cullins, John Lamphier, Kieran Leahy, James Kelly and James McEvoy. A School was built by the Company in Kyle Lane about 1826 and lasted until the old two story building was constructed in 1887.

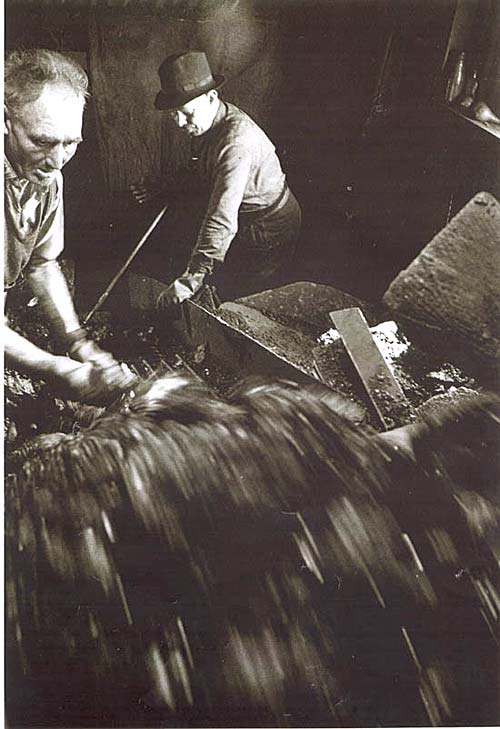

During the Famine years the Company was mining at a loss, the miners were kept in employment. Production recorded for the years 1843 to 1853 totals 51,787 Tonnes Coal and 284,019 Tonnes duff (culm). Apart from mining and farming there were few other ways of making a living in this remote, hilly district . A decline in coal mining came around 1900 and mining almost completely ceased in 1919, apparently because explosives could not be obtained. Locals however continued to sink shafts called ‘bassets’, the landowner getting a percentage of the profit and free coal. Mr. William Young worked 1.07 acres in the Lickfinn and Glengoole South areas around this time and is recorded as recovering 3,200 tons.

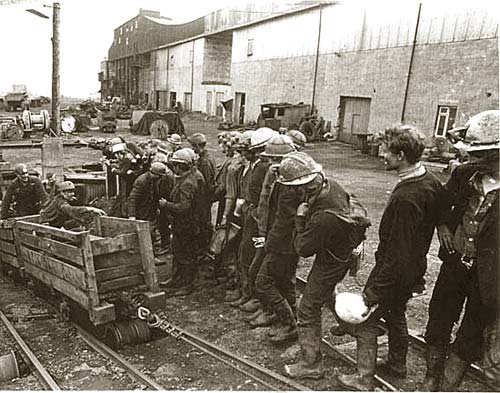

In 1941 a State mining company called Mianraí Teoranta was established and, along with a number of other ventures around the country, acquired the rights to develop the Slieveardagh Coalfields under the authority of the Minister of Industry and Commerce. The Slieveardagh Coalfield Development Bill, 1941 was introduced in the Daíl and passed on April 3rd 1941. A mine was opened in Ballynonty in August of the same year employing up to 100 men. The manager was a man named Mr. McGlucky from Scotland. They also worked in Lickfinn and continued during the war years but found both projects uneconomic and they were abandoned in favour of the Copper basin in September 1948. This transition took some months as they had to move the entire operation, including buildings, machinery etc. Not long after its’ establishment, Copper Colliery was renamed Clashduff Colliery in order “to avoid confusion with the metal”! Then in January 1949 it was again renamed Ballingarry Colliery.

In 1941 a State mining company called Mianraí Teoranta was established and, along with a number of other ventures around the country, acquired the rights to develop the Slieveardagh Coalfields under the authority of the Minister of Industry and Commerce. The Slieveardagh Coalfield Development Bill, 1941 was introduced in the Daíl and passed on April 3rd 1941. A mine was opened in Ballynonty in August of the same year employing up to 100 men. The manager was a man named Mr. McGlucky from Scotland. They also worked in Lickfinn and continued during the war years but found both projects uneconomic and they were abandoned in favour of the Copper basin in September 1948. This transition took some months as they had to move the entire operation, including buildings, machinery etc. Not long after its’ establishment, Copper Colliery was renamed Clashduff Colliery in order “to avoid confusion with the metal”! Then in January 1949 it was again renamed Ballingarry Colliery.

By 1950 the mines were again operating at a loss and a Mayo man, Mr. Tommy O’Brien is reported to have purchased the ailing operation from the state in February 1952 for £50,000. Apparently he had cleared his outlay within 12 months, having disposed of the huge amounts of mine deposits on the surface, installed new pumping equipment to overcome flooding and discovered a new seam of top quality anthracite.

By 1950 the mines were again operating at a loss and a Mayo man, Mr. Tommy O’Brien is reported to have purchased the ailing operation from the state in February 1952 for £50,000. Apparently he had cleared his outlay within 12 months, having disposed of the huge amounts of mine deposits on the surface, installed new pumping equipment to overcome flooding and discovered a new seam of top quality anthracite.

In 1962 Mr. O’Brien also set up a site at the Commons which was operated for 12 months and for which he apparently received £60,000 in grants.

Also during the 1960’s it is reported that at least

£1/2 million were invested from personal funds, State grants and loans. However despite such investments the Company went into receivership in November 1967 and was operated as such for the next four years . In 1969 the same company made attempts to develop opencast sites both in Knockanglass and Ballyphilip, approximately 35 and 15 acres respectively, leased from local farmers. Both were fruitless efforts abandoned after less than 12 months in operation.

On January 15th 1971, miners’ wage cheques that had been made out to other businesses in South Tipperary during a bank dispute, bounced when they were presented for lodgement. The mines were in financial difficulties again and workers were employed on a week-to-week basis. The company eventually went into liquidation and finally ceased trading in September 1972, although the mines continued to be pumped out until August 1973 when it was finally accepted they were no longer operational. 180 miners lost their jobs and equipment which was “worth a fortune” was abandoned to the waters in the flooding pits. According to the miners; a coal plough bought in 1969 for £85,000, 22 electric pumps, miles of cable and much more was included.

On January 15th 1971, miners’ wage cheques that had been made out to other businesses in South Tipperary during a bank dispute, bounced when they were presented for lodgement. The mines were in financial difficulties again and workers were employed on a week-to-week basis. The company eventually went into liquidation and finally ceased trading in September 1972, although the mines continued to be pumped out until August 1973 when it was finally accepted they were no longer operational. 180 miners lost their jobs and equipment which was “worth a fortune” was abandoned to the waters in the flooding pits. According to the miners; a coal plough bought in 1969 for £85,000, 22 electric pumps, miles of cable and much more was included.

Glimmerings of hope were again on the horizon when in 1978, the soaring price of oil made industrialists realise the viability of coal as a source of energy. Pat Keating and Gilbert Howley, trading under Kealy Mines Ltd., commenced excavations in Lickfinn, Ballynonty, about 3 miles (4.83 km) from the previously worked collieries at Gurteen, where they apparently found a new vein of high grade anthracite. The mining lease covered 9 miles square (23.31 km square) in an area that had not been mined for 30 years. Approximately 50 people were employed by Kealy Mines but once again lack of necessary capital resulted in a decision to sell the mines.

The operation was acquired in 1982 by a Canadian based public company, Flair Resources Ltd. marketing under the name Tipperary Anthracite Ltd. The attraction was apparently the rising price of anthracite which had risen from £10/ton in 1971 to £160/ton in 1982. By 1983 eighty people were employed but despite IDA (Industrial Development Authority) investment in the company, a lack of liquidity began to become evident. Flooding became a constant problem and the machinery was not there to deal adequately with it. Weeks of production were lost, while pumping with relatively poor equipment. In December Tipperary Anthracite Ltd. went into liquidation and Flair Resources (Ireland) Ltd. followed in January 1985. Large debts were left behind and a hugely controversial situation ensued with allegations of fraudulent dealing leading to an enquiry. On May 20th 1989 another company, Emerald Resources plc. obtained a state mining lease for 602 ha of the Slieveardagh Coalfield based at Gurteen. This lease was given for 20 years. However this company was again unsuccessful and lasted less than two years.

The operation was acquired in 1982 by a Canadian based public company, Flair Resources Ltd. marketing under the name Tipperary Anthracite Ltd. The attraction was apparently the rising price of anthracite which had risen from £10/ton in 1971 to £160/ton in 1982. By 1983 eighty people were employed but despite IDA (Industrial Development Authority) investment in the company, a lack of liquidity began to become evident. Flooding became a constant problem and the machinery was not there to deal adequately with it. Weeks of production were lost, while pumping with relatively poor equipment. In December Tipperary Anthracite Ltd. went into liquidation and Flair Resources (Ireland) Ltd. followed in January 1985. Large debts were left behind and a hugely controversial situation ensued with allegations of fraudulent dealing leading to an enquiry. On May 20th 1989 another company, Emerald Resources plc. obtained a state mining lease for 602 ha of the Slieveardagh Coalfield based at Gurteen. This lease was given for 20 years. However this company was again unsuccessful and lasted less than two years.

The Ballingarry coal mines always appeared to have an adequate market for its coal products, but the succession of owners, coupled with glaring management errors, left the mine with huge inherent debts and severe capital limitation. None of the companies were big enough to tackle the financial problems of the mine and provide the investment necessary to bring it back to a sound footing. In the end this cost the mine its future and left a series of complications for any future developers regarding remaining debts, rights to the mining lease, land ownership etc.

In a 1971 report on the Gurteen mine Duffryn stated that no mine operates consistently at its’ potential output over a lengthy period. Production may be reduced due to a number of factors including the following:

- Difficult mining conditioned due to geology, poor strata control, water, faults, etc;

- Inadequate research into such local conditions;

- Inadequate equipment/equipment maintenance leading to breakdowns;

- Inefficient management/supervision;

- Low manpower performance due to lack of incentive or absenteeism.

It appears that each of these factors may have contributed to the end of the coal mining era in Tipperary. However it is also fair to suggest that over enthusiasm in the area for coal mining may have blinded those involved to the fact that for the amount of capital required to make the operation viable, the amount of readily recoverable proven reserves would not be adequate.

The following is a list of the location of Mines/Shafts in Slieveardagh

- Blackcommon,

- Boulea (Boulintlea),

- Ballyphilip,

- Ballinastick

- Ballingarry Lower,

- The Commons,

- Coalbrook,

- Clashduff

- Curraheenduff,

- Coolquill,

- Earlshill,

- Foilacamin,

- Gurteen,

- Graiguemane,

- Knockabritta

- Knockalonga,

- Knockilterra,

- Lickfinn

- Mardyke,

- Monslatt,

- NewPark