Pottlerath-&-Gortfree

When the Psalter of Cashel Changed Hands After a Battle.

Thomas (“Black Tom”) Butler, 10th Earl of Ormond

One might be forgiven for thinking that the Anglo-Irish lords of the Middle Ages spoke no Irish, or that if they did they had no real interest in Irish culture. Well, think again. When King Richard II came to Ireland in 1394 the then Earl of Ormond (Butler) interpreted the Irish chiefs for him. This Earl was James, third Earl of Ormond; he was influential in bringing the Irish septs, most notably O’Brien, prince of Thomond, to Dublin to submit to Richard. King Richard used his visit to strengthen the loyalty of the Anglo-Irish community, Butlers and FitzGeralds included; but he was happy to receive submissions from the native Irish. He was well aware that the medieval lordship extended only to the Pale around Dublin and what is sometimes referred to as the Second Pale, the Butler (earls of Ormond) district of South Leinster and into Tipperary.

Edmund FitzRichard was a grandson of James, Earl of Ormond. (His father Richard was named after the King who came over in 1394.) This Edmund (FitzRichard) Butler caused the Psalter of Cashel to be made. The manuscript is a transcription of Fenian cycle material, saints lives, genealogies and much historical and theological material. The Psalter changed hands at the battle of Piltown, near the river Suir, in 1462, falling into the possession of Thomas FitzGerald, Earl of Desmond who defeated the Butlers under the leadership of the man who commissioned the book, Edmund FitzRichard. We have this information from what is written by both owners in the margins of the manuscript – and proof that Irish was the language they used in ordinary conversation. The manuscript is now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

The Ormond earls were absentees from the 1450s. They became allied with the Boleyns (the family of Henry VIII’s second wife), which sealed their English allegiance and their embrace of the religious revolution at a time when their great rivals to the west and south, the Geraldines, remained Catholic and defiantly Irish. The main Ormond line remained Protestant, but when James FitzMaurice FitzGerald raised the standard of Catholic counter-revolution in 1569 he was joined by the (Catholic) brothers of the current Earl of Ormond. This individual, Black Tom Butler, was a direct descendant of Edmund FitzRichard Butler.

James, third Earl of Ormond, mentioned at the beginning of this article, was the brother-in-law of that earl of Desmond the subject of the recent book from Maire Mhac an tSaoi: Gearóid Iarla. Gearóid is well known for the Gaelic poetry he wrote and the poetry written for him by Goffraidh Fionn O Dálaigh. The other language used was French: his father, the first Earl of Desmond, writes in French when corresponding with the Government (which we find in the printed State Papers). Gearóid is a legendary figure, said to sleep beneath the waters of Lough Gur, only to appear every seven years to ride his horse over the lake.

About 450, Saint Patrick preached at the royal dun and converted king Aengus. The Tripartite Life of the saint relates that while “he was baptising Aengus the spike of the crozier went through the foot of the King” who bore with the painful wound in the belief “that it was a rite of the Faith”. According to the same authority, twenty-seven kings of the race of Aengus and his brother Aillil ruled in Cashel until 897, when Cerm-gecan was slain in battle. There is no evidence that St Patrick founded a church at Cashel, or appointed a Bishop of Cashel. St Ailbe, it is supposed, had already fixed his see at Emly, not far off, and within the king’s dominions. Cashel continued to be the chief residence of the Kings of Munster until 1100, hence its title, “City of the Kings”. Before that date, there was no mention in the native annals of any Bishop, or Archbishop of Cashel. Cormac MacCullinan is referred to, but not correctly, as Archbishop of Cashel, by later writers. He was a bishop, but not of Cashel, where he was king. The most famous man in Ireland of his time, but more of a scholar and warrior than an ecclesiastic, Cormac has left us a glossary of Irish names, which displays his knowledge of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and the “Psalter of Cashel”, a work treating of the history and antiquities of Ireland. He was slain in 903, in a great battle near Carlow.

Expert bibliographers have described book thus: “The sumptuous initials of this book are not more or less servile repetition of twelfth-century work. the work of the scribe also is dazzling. He plays like a virtuoso with various sizes of script, the larger size having a majestic decorative quality. The contents are no less remarkable; the ‘Martyrology of Óengus’, the ‘Acallam na Senórach’ and a dindsenchus. … The foliage pattern is probably inspired by foreign models, but is so completely integrated that the borrowing is only realised on second thoughts. The initials are large, bold, and drawn in firm lines and bright colours”

COPIED

The story of The book of Pottlerath starts with James Butler, the 4th Earl of Ormond, known as the White Earl who had a great interest in archaeology and history. He started work on the manuscript in Kilkenny. When he died of the plague in 1452 he left the manuscript, not to his son and heir, but to his nephew Edmund Butler of Pottlerath, son of Richard. It quickly became known as the The Book of the White Earl and consists of 12 folios inserted into Leabhar na Rátha (The Book of Pottlerath).

Butler was known to have been strongly Gaelicised. He was an Irish-speaker and seems to have been the very first of the Anglo-Irish lords to appoint a brehon, Domhnall Mac Flannachadha, for his service. Around 1450 Edmund Butler built a castle a few fields away from the site of the original Dun or fort in Kilmanagh. The church, which was near the castle, may have been built a few years later. In an article in the Archaeological Journal of 1852, mention is made of the Columbarium of Pottlerath – this was the dovecot, which is still in existence.

In 1453 Edmund decided to enlarge the manuscript, incorporating the earlier work and commissioned his scribe Sean Buidhe O’Cleirigh with fellow scribes to produce the manuscript which was called the Book of Pottlerath. It was completed a year later, in 1454.

Psalter of Aengus Mac Nathfrach, King of Cashel “Oxford the 9th of August 1673”

“This book is a famous copy of a great part of the Book of St. Mochuda of Cong, in which is contained many divine things, most of which documents the antiquities of the ancient houses of Ireland, a catalogue of their Kings, of the coming of the Romans into England, of the coming of the Saxons, and of their lives and regimes; a notable calendar of the Irish Saints of the Roman breviary until that time; a catalogue of the Popes of Rome; how the Irish and the English were converted to the Catholic faith; with many other things, as the reader may find, and so understanding what they contain let him remember. – Tully Conry”

Thus is recorded on a note pasted on the inside of the cover of a copy of the Psalter of Cashel written by Aengus Mac Nathfrach, King of Cashel, Copied in 1453 for Edmund Mac Richard Butler in Pottlerath by Seagan Buidhe O’Cleirigh. And now preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

The Story of Slieveardagh and its Christian heritage begins with the Baptism of Aengus Mac Nathfrach at Cashel. A celebrated anecdote is told about this King Aengus. It is said that when St Patrick was conferring the Sacrament of Baptism upon him he accidentently laid the crosier on the Kings foot. The crosier pierced his foot, causing it to bleed profusely. So great, however, was the Kings devotion, that he did not make any sign of uneasiness, but patiently bore the pain, thinking it was part of the ceremony. ‘This crosier (the celebrated Irish relic known as the Bachal-Iosa, i.e., the Staff of Jesus) was preserved in Armagh until the English invasion (Cromwell) when it was brought to Dublin and kept at Christ Church Cathedral. But alas! At the time of the reformation it was publicly burned in the streets of the city’.

The first recorded missionary to Ireland was Palladius, who was probably from Gaul [France]. He was sent by the Pope to be bishop to the “Irish who believe in Christ”. Patrick himself stated that Palladius’ mission was a failure. However, other historical documents from outside Ireland indicate that the mission of Palladius was very successful, at least in Laigin (Leinster), and that he set up a number of churches. Tradition says that Palladius’ visit to Ireland was in the year 431.

(FRAGMENT FROM THE BOOK OF POTTLERATH.)

We are told in Historical Geographies that during the century before the Christian Era there was a regular movement of population between the districts now known as Munster and Leinster, by way of the gap ‘between Slieveardagh and Slievenamon. The passage was one of the chief routes between Tara and Cashel. Later the district became the scene of many conflicts between the Norse men from Scandinavia and the native Irish. Later still it was frequently the battleground for the war-loving Ormonde and Geraldine landowners. Nowadays, happily, the rivalry between the sturdy combatants of the ancient principalities of Cashel and Ossory is exercised only on the hurling and football fields.

In the Ossory Archaeological Society publications, papers attributed to Dr James Lanigan (1779 -1812) Bishop of Ossory deal with the Parish of Kilmanagh. According to Dr. Lannigan there are two patron Saints of Kilmanagh -Saint Edán or Enda whose feast is assigned to the 31st Dec and St. Natalis, or Naul, – Nailé ‘as Gaeilge’, whose feast day is set down in the Martyrology (recorded calender of events) of Tallagh as the 31st July. It is very probable that St Nathalis was the son of Aengus Mac Nathfrach, King of Cashel (killed 490). Dr Lanigan says that little or nothing would be known about Nathalis were he not highly praised in the lives of St. Senan of Inniscathy (Scattery Island at the Mouth of the Shannon), who, when young, was a pupil of his, having been directed to his monastery by the Abbot Cassidus. This monastery was situated in Dún-Aengusa-Mac Nadfraich called after the first Christian King of Munster who resided in Cashel; was later known as Rath a’Photaire (Rath of the potter) later anglicized to Pottlerath a townland near the Munster River in Kilmanagh Parish, Co. Kilkenny.

In the metrical life of St Senan (translated) we read: – “In a vision, an order is given By the Lord of Heaven, to the abbot Cassidan To send the novice to the illustrious Abbot Nathalis To be fully instructed, under his rule and discipline, Even at that time, Nathalis’ name was well known to fame With him a large community dwelt in religious unity A hundred and fifty brethren, learned and holy men”

In the metrical life of St Senan (translated) we read: – “In a vision, an order is given By the Lord of Heaven, to the abbot Cassidan To send the novice to the illustrious Abbot Nathalis To be fully instructed, under his rule and discipline, Even at that time, Nathalis’ name was well known to fame With him a large community dwelt in religious unity A hundred and fifty brethren, learned and holy men”

This number must have increased very much, if there is any truth in the following story. It is written that the monks of Dún-Aengusa-Mac Nadfraich paid a visit to their brethren at the monastery of Gort-friogh – ‘this is the town land of Gortfree beside The Munster River in Ballingarry Parish, the river divides the modern Parishes of Ballingarry and Kilmanagh – Counties Tipperary and Kilkenny – as well as the provinces of Munster and Leinster. According to local folklore the site of this monastery is at the location of an old graveyard now dis-used’. When they arrived there the Abbot observed he had forgotten his breviary. Word was immediately sent back from one to the other by the monks, whose long line reached Pottlerath about two miles distant, and the breviary was forthcoming without delay.

St Naul flourished about the year 520, his death is assigned to the 27th January 564. From the following references, found in the annals of the Four Masters, Pottlerath must have been a place of importance and distinction in ancient times.

Under the year 780 we read: “The fifteenth year of Donnchadh Maeloctraigh, son of Conall, Abbot of Kilcullen and scribe of Cill-manach, died.” At the year 802 “Lemnatha Cill-manach died”. In the year 843 “Beasal, son of Caingne, Abbot Cill-manach died.

According to Dr. John O Donovan, the ancient name of Pottlerath was Dun-Aengusa-Mac Nadfraich -i.e., the fort of Aengus Mac Nadfraich, the first Christian King of Munster. It is worthy of note and very significant too, that Naul, the patron saint of Kilmanagh, was son of this same prince; and also that a holy well, known as Tobernedaun, or St Enda’s well, preserves the name of St Enda of Arran, whose sister, Sant, was wife of Aengus, and mother of St Naul. There are cures documented in the Ossory papers attributed to the waters of this well. These sites are on the South Eastern end of the Slieveardagh hills

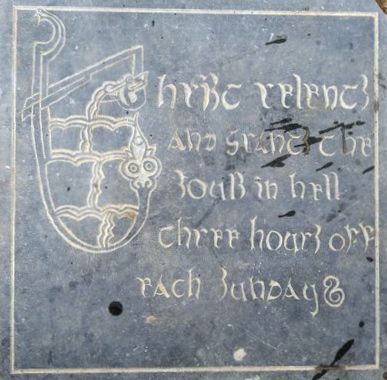

“Christ Relents and Grants the Souls of Hell Three Hours off each Sunday” – This quote is taken from the Book of Pottlerath. This illuminated manuscript was also known as the Psalter of Cashel or the Book of The White Earl. This manuscript is now housed at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

James Butler, the 4th Earl of Ormond, was known as the White Earl. He had a great interest in archaeology and history. He started work on the manuscript in Kilkenny and when he died he left the manuscript, not to his son and heir, but to his nephew Edmund Butler of Pottlerath, son of Richard.

The book was completed in 1454. After a battle in Piltown which saw the Butlers defeated, the book was handed over to Thomas Fitzgerald, 8th Earl of Desmond, in ransom for Butler’s release.

It took several generations before the book was returned to the Butler family, probably as part of the dowry when the 9th Earl of Ormond married the daughter of the 10th Earl of Desmond. The book was eventually bequeathed to the Archbishop of Canterbury who was Chancellor of the University of Oxford. He in turn gave it to the University for the Bodleian Library in 1636.