Earlshill

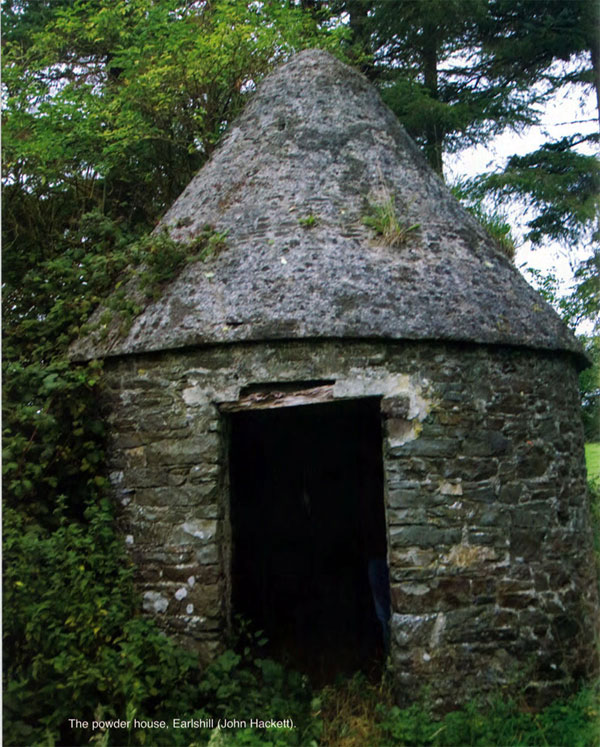

Earlshill was not a planned village but had its own police barracks and public house.There were 67 houses in the townland in 1850, the majority valued under £1 and located on the ‘old road’ on the Langley/Going estate’s boundary. In 1848 a steam engine was transferred from Mardyke to Earlshill. It was one of the few townlands in Slievardagh to increase its population in the decade of Famine 1841-1851 from 340 to 372. Its mining artefacts included an engine house. now disappeared and probably incorporated into a boundary wall, the remains of the reservoir which held the water for the engine boiler, a powder house (built in corbelled style) and a ventilation chimney, all of which survive. Folklore has it that a sod house under the chimney had a fire which helped create a draught to aerate the pit in the early 20th century.

Patrick Leahy had almost 300 bassets marked on his map of 1824. Problems with water, ventilation and roof supports meant that the basset was shallow in depth and could only command a short distance underground. They could, however, be profitable as the costs related to labour and a royalty to the landowner. They were worked by family groups such as Ivers, Cleere’s and Pollard’s and so on were such – or companies (referred to as crews in the early nineteenth century). The collapse of a basset pit in 1937 resulted in the death of Paddy Ivers. The last ‘native’ Slievardagh mining manager in Earlshill was his nephew, Michael Ivers, who began working with his company in Lickfinn in 1949 before moving to Glengoole South in 1950. When the mining rights were leased by the state to Thomas O’Brien in 1952, Ivers was forced to close his operation.

The Mining Company of Ireland took possession ‘of Mr Going’s extensive coalfield in Earlshill and Ballyphillip with free use of his level’ for £500 per annum together with his interest in The Commons at 1/8th of the royalties on 4 April 1845. On 20 October in the same year Martin Morris, an underground steward, was shot, presumably by contractors annoyed at the introduction of direct labour by the new company. The Company publicised its wages of 2s/6d for operators and 2s/ for labourers in contrast to the 8d paid to agricultural labourers.

Mining persisted in the Earlshill Basin after the departure of the Mining Company of Ireland in 1886. The Slievardagh Colliery Company’s manager William (Billy) Young is well remembered in the district and had a pit in Ballinastick named after him. Throughout Slievardagh’s mining history basset pits -the word basset comes from the geological term meaning outcrop – were used to extract the coal/culm close to the surface. Patrick Leahy had almost 300 bassets marked on his map of 1824. Problems with water, ventilation and roof supports meant that the basset was shallow in depth and could only command a short distance underground. They could, however, be profitable as the costs related to labour and a royalty to the landowner. The collapse of a basset pit in 1937 resulted in the death of Paddy Ivers. The last ‘native’ Slievardagh mining manager in Earlshill was his nephew, Michael Ivers, who began working with his company in Lickfinn in 1949 before moving to Glengoole South in 1950. When the mining rights were leased by the state to Thomas O’Brien in 1952, Ivers was forced to close his operation.

Mining persisted in the Earlshill Basin after the departure of the Mining Company of Ireland in 1886. The Slievardagh Colliery Company’s manager William (Billy) Young is well remembered in the district and had a pit in Ballinastick named after him. Throughout Slievardagh’s mining history basset pits -the word basset comes from the geological term meaning outcrop – were used to extract the coal/culm close to the surface. Patrick Leahy had almost 300 bassets marked on his map of 1824. Problems with water, ventilation and roof supports meant that the basset was shallow in depth and could only command a short distance underground. They could, however, be profitable as the costs related to labour and a royalty to the landowner. The collapse of a basset pit in 1937 resulted in the death of Paddy Ivers. The last ‘native’ Slievardagh mining manager in Earlshill was his nephew, Michael Ivers, who began working with his company in Lickfinn in 1949 before moving to Glengoole South in 1950. When the mining rights were leased by the state to Thomas O’Brien in 1952, Ivers was forced to close his operation.

As in England mining was carried out in Slievardagh by the landowners, such as the Goings, Langleys, Barker -Ponsonbys and Vere Hunt through the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Ballyphillip House was the residence of the Goings who worked Earlshill colliery before leasing it to the Mining Company of Ireland. The house was demolished in the 1930s. Coalbrook House, was the residence of the Langley family, who had collieries at Lisnamrock, The Acres and Knockalonga. This family also leased rights to the Mining Company but began small-scale mining again after its demise. Kilcooley House belonged to the Ponsonby family whose mining interests were located to the east of the field. Richard Sutcliffe, who worked a mine in Kilcooly in 1883, emigrated to Wakefield, England where he developed the first coal cutting machine and underground conveyor system. Vere Hunt, who lived at Sherbourne House on his Glengoole Estate, has left a vivid account of his coal mining enterprises on the hills above his residence in the early decade of the nineteenth century. The Mining Company of Ireland erected Coalfield House at The Commons for its manager in the 1850s. Thomas O’Brien invested the profits from the Gurteen enterprise in the 1950s in purchasing the imposing Woodrooff House near Clonmel.

Mining in Slievardagh was localised and small scale in the years from 1900 to 1940. But the outbreak of World War Two disrupted coal imports to Ireland and focused attention on native resources. In May 1941 the Sllevardagh Coalfield Development Company was formed but was superseded by Mianrai Teoranta in June 1945. Ballynonty was developed north of Mardyke in the former demesne of the Going Estate, despite local opinion that better prospects were present at the centre of the basin. At its peak Ballynonty mine employed 170 men and had a hostel for 80 men. The photographic record, by Michael Keating, Clonmel, of the mine’s development is an unique source. It was the first Slievardagh mine to use electricity for powering haulage and pumping of water but the colliers still worked in bad conditions. Another innovation was that candles were replaced by carbide lamps to provide light underground.

Some of Slievardagh’s legendary miners such as ‘King’ Cleere of The Commons worked here and he has left a valuable written account of his time in Ballynonty. Coal was transported to the rail station at Laffansbridge and distributed from there to towns and cities. Apart from the managers and miners, the carters, who transported coal and culm by horse-drawn vehicles, were central figures in the mining industry before the advent of motorised transport.

Usually owners of small farms, ‘earring’ coal was the preserve of families such as the Caseys, Daltons and Dorans. They travelled in bitter, winter weather to towns such as Callan and Cashel and the horse, which hauled coal in winter, pulled the plough in spring and the hay tedder in summer. Jim Kennedy, folklorist of Slievardagh, remembered how one enterprising man hired out his massive horse to help the carters negotiate the steep slopes downhill to the lowlands.

(Shelbourne House original home of de Vere Hunt)