Mardyke Mine

An outlier of Westphalian rocks, on the border of counties Kilkenny and Tipperary, which are folded into a series of near parallel synclines. In consequence of this, of the nine seams present, only the lowest two, the Glengoole No.1 and No.2, are present throughout. Except for in the cores of synclines, the other seams have been mostly eroded. All the coal is anthracite, and the Glengoole No.2 seam was of excellent quality, with low sulphur (0.8%), low ash levels (4.0%) and high calorific value. It was typically 18 inches thick, but was prone to localised thickening and thinning, as well as crushing of the coal, caused by thrusting. The latter resulted in a high proportion of coal fines (duff or culm) in some of the mined coal. At Ballynonty, the duff content was typically 80 – 100%

Mining dates from at least the mid-seventeenth century, but may be earlier. Until the nineteenth century it was small-scale, often land owners serving their own needs.

(NOTE – All are Listed Buildings)

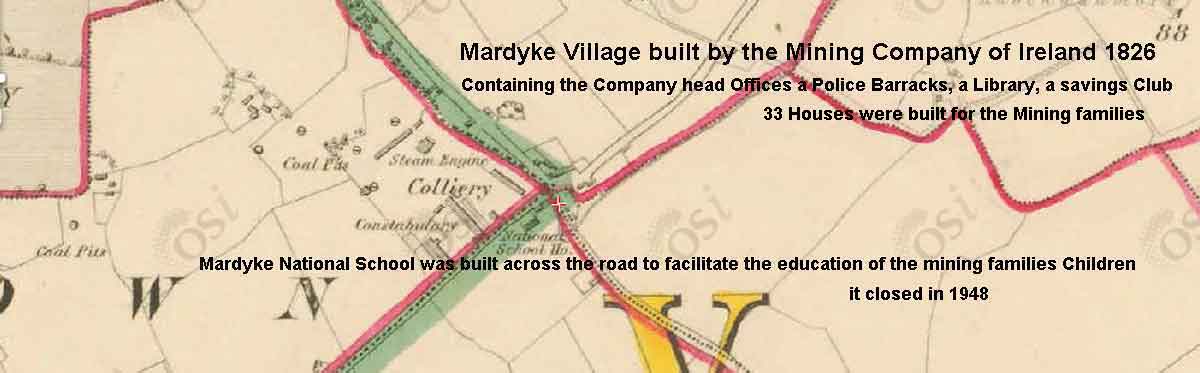

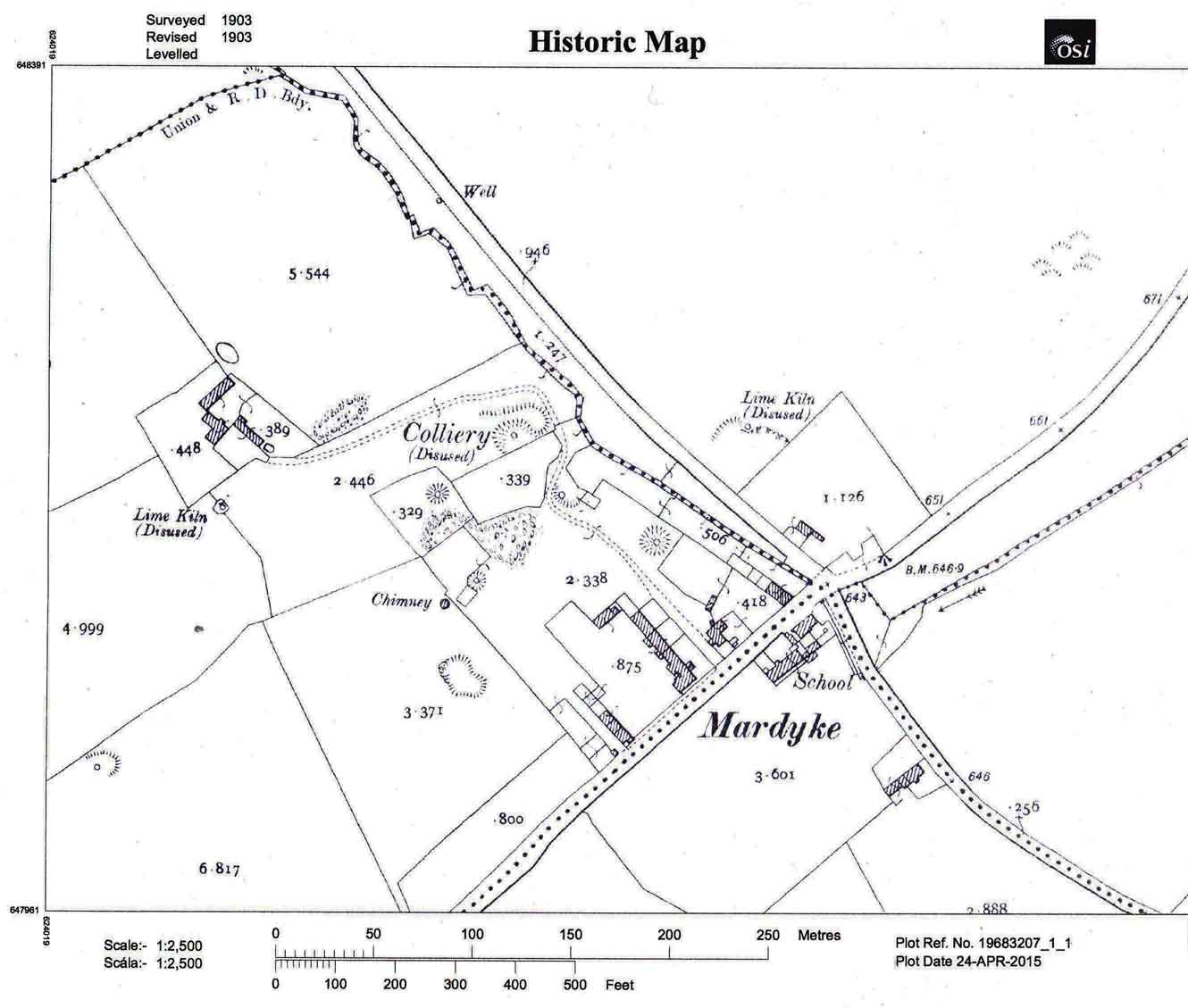

MARDYKE

THE MINING COMPANY OF IRELAND 1824

In 1824 the Mining Company of Ireland was formed by an Act of Parliament. In 1826 the Mining Company opened extensive collieries at Mardyke, in the parish of Killenaule. The Company leased the land for 21 years from three landowners, Palliser, Tighe and Ponsonby . At this time a steam engine was providing power for the workings and the company built an engine house and 9 dwellings for workmen. In 1829, 10 additional houses were built for workers. In 1831 the lease was extended for 41 years and in 1832, 6 more houses were built for the miners. Offices, a police barracks and a school, were also built and Mardyke became the first mining village in Ireland.

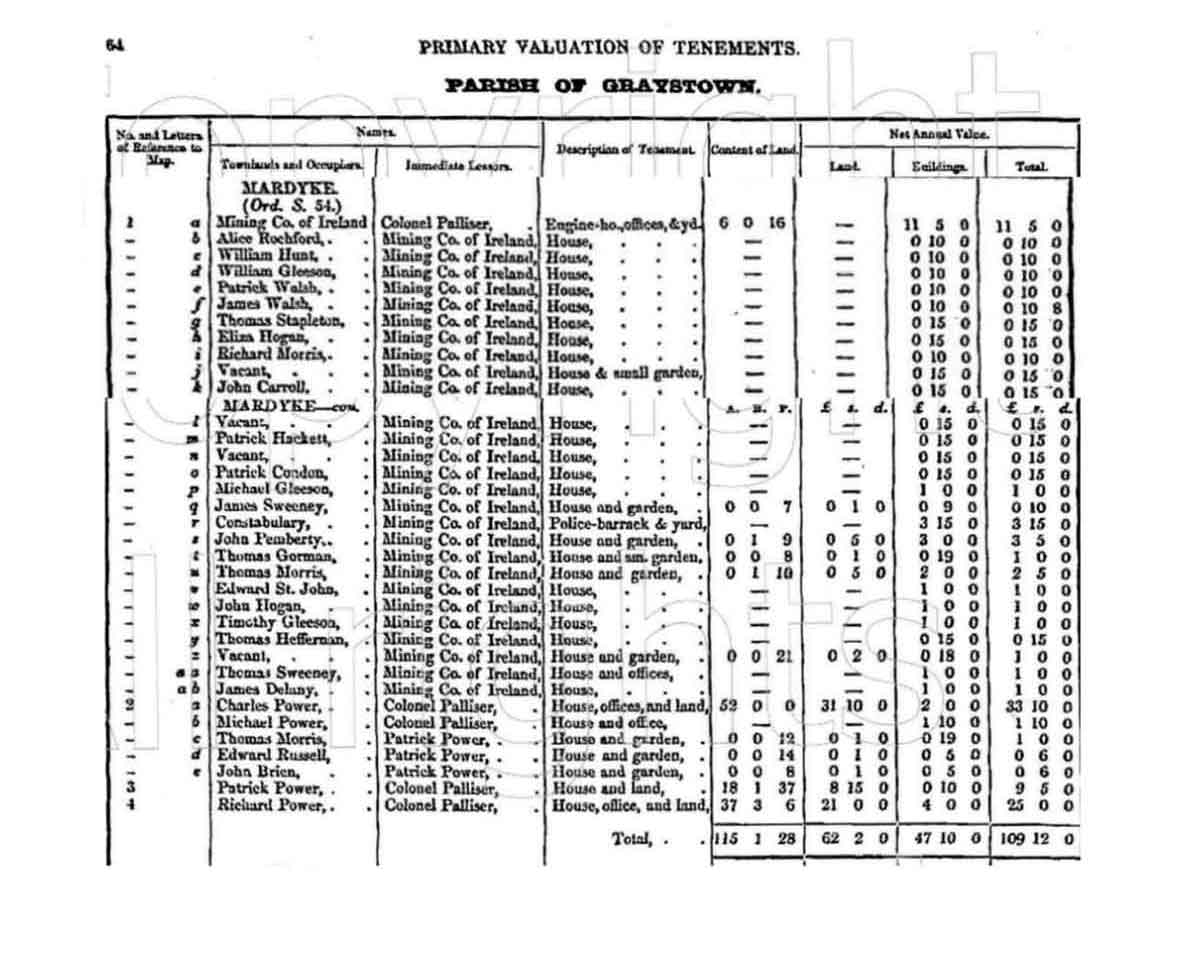

The Primary valuation of Tenements for the area reports, that, by 1848 there were 33 houses in this village, three were vacant at the time of the survey. The families who occupied the houses were;- Alice Rochford, William Hunt, William Gleeson, Patrick Walsh & James Walsh, Thomas Stapleton, Eliza Hogan, Richard Morris, John Carroll, Patrick Hackett, Patrick Condon, Michael Gleeson, James Sweeney, John Pemberty, Thomas Gorman, Thomas Morris, Edward St John, John Hogan, Timothy Gleeson, Thomas Heffernan, Thomas Sweeney, James Delaney, Charles Power, Michael Power, Thomas Morris, Edward Russell, John Brien, Patrick Power and Richard Power.

All the houses had slate roofs, the village was divided into three streets, Puddle Street also known as River Street, Middle Street and High Street.

GRIFFITH VALUATION 1850

The area was then known as ‘The Found’ and still is today.

The area was then known as ‘The Found’ and still is today.

In 1833 mining ceased in Mardyke, uneconomic due to the natural crushing of the seams resulting in a production ratio of 30% coal to 70% duff (culm) the Company extended its’ operation to Foilacamin and The Commons. In 1844 the Company leased the Earlshill and Ballyphilip collieries from Mr. Going. “This would place in the company’s possession the best anthracite coalfield in Ireland”.

INSPECTORS REPORT

THE COLLIERIES IN THE COUNTY OF TIPPERARY

22, Richmond Hill,

Rathmine: Road,

Dublin

10th June 1841.

- THE Mining Company of Ireland have three collieries in this county, situated from about two, to SIX miles from Killenaule. I first visited Mardyke Colliery, which is the nearest to Killenaule and where the agent for all of them, Mr. Robert Nicolson, resides. At this pit there are no children employed, and but two or three young person, and no females at all; indeed females are not employed in any of the collieries in this county.

- Mr. Nicolson stated that they had a few young boys who were employed under ground, merely opening and shutting the doors after the wagons had passed through in order to keep the fresh air in its regular course round the mine; that for the other work, as “ hurries,” they required strong able young men of from about 18 years old and upwards.

- The hurries, fillers, and colliers are generally partners in the same bargain.

- At the Sleive Ardagh Colliery, which is about six miles distant, but under the same management and direction, there are about 20 young men under 18 years of age employed, but no children; but the day I visited it was fair-day at Ballingarry, close by, and the people were not at work. There also were two or three little boys employed as at the other pit, opening and shutting the doors, after the waggons had passed.

- At the Mardyke Colliery is a temperance hall, a lending library and reading room, a saving society, and a school-room about to be built by subscription of the company. and colliers.

- There are also neat ranges of buildings built by the company as residences for the colliers.

- Altogether, at the company’s pits, there are about 400 people employed. There is a great deal of sulphur amongst the coal, so much, that, at that used for the steam-engines, I found it almost impossible to enter the engine-house from the suffocating smell.

- In this neighbourhood, between the two principal pits of the company, there is a very extensive colliery, called the Coolbrook, belonging to — Langley, Esq., which I visited, but, being fair-day close by, the people were not at work ; the machinery connected with the pumping was also so much out of order that they expected to stop work for a week or two.

- Mr. Nasmyth, the agent, told me they did not employ children—that they were of no use ; they required strong able lads of 17 or 18 years old to do their work, of whom about 80 were employed. They work from eight to twelve hours daily, and, as the work is all task-work, there are no regular meal-times ; but he informed me that the people generally took bread with them when they had their meals under ground.

- There are about 400 people employed at this pit.

- There is no school attached to the works, neither is there a sick-fund, or doctor’s fund.

- On my remarking upon the high price of the coal at the pit mouth (lOd. a cwt. for the best), Mr. Nasmyth said, in consequence of the great difficulty in getting the coal, it hardly paid a remunerating price, not more than 2. per cent. interest on the capital employed ; that the seam of coal was generally very small, and the rock they had frequently to work through was exceedingly hard.

- There are in all directions hereabouts small shafts opened, which are worked only until they come to the water, for the sake of the culm or small coal, used for burning limestone, and by the poorer people for fuel.

- I believe there are two or three other rather extensive collieries hereabouts but I had not time to visit them all.

- It is a subject worthy of remark, that at all the mines I have visited the managing directors are Englishmen, generally Cornishmen; and at the collieries in Tipperary the managing agents are Scotchmen.

- I am told the Irish are not clever at sinking shafts, but are pretty good miners, so long as they have some experienced Cornishmen working with them, or to direct them—being comparatively a new field for them, they do not generally understand the operations of mining, except the simple one of getting the ore or coal.

I have the honor to be, Gentlemen,

Your very obedient humble servant,

FREDERICK ROPER, Sub-Commissioner

<——————————————————————>

In 1826, however, the Mining Company of Ireland opened collieries at Mardyke, and used a steam engine for pumping. As well as an engine house, the company built at least 25 houses for its workers, offices, a police barracks and a school.

Mardyke closed in 1833 because of the high proportion of duff, but undeterred the company had mines at Foilacamin and The Commons. The company also leased Earlshill, where a chimney, magazine and the manager’s house survive, and Ballyphilip collieries in 1844 and kept going until around 1890.

Mining had died out by 1920, but in 1941 Mianraí Teoranta, a state mining company, reopened Ballynunty and Lickfinn collieries. They both proved uneconomic, however, and so operations were moved to the Copper basin in September 1948. At first called Copper, this colliery was soon renamed Clashduff. In January 1949 it became Ballingarry and worked until 1957.

Gurteen worked from 1957 to 1972, and its large spoil heap remains. The last mining in the area was the sinking of a drift mine at Lickfinn in 1978. It worked until 1990.

An engine house and chimney at Mardyke are probably survivals from the 1859-1865 reworking. A ventilation chimney still stands in fields near Ballingarry colliery, and there is an engine house and chimney at Coalbrook

An engine house and chimney at Mardyke are probably survivals from the 1859-1865 reworking. A ventilation chimney still stands in fields near Ballingarry colliery, and there is an engine house and chimney at Coalbrook

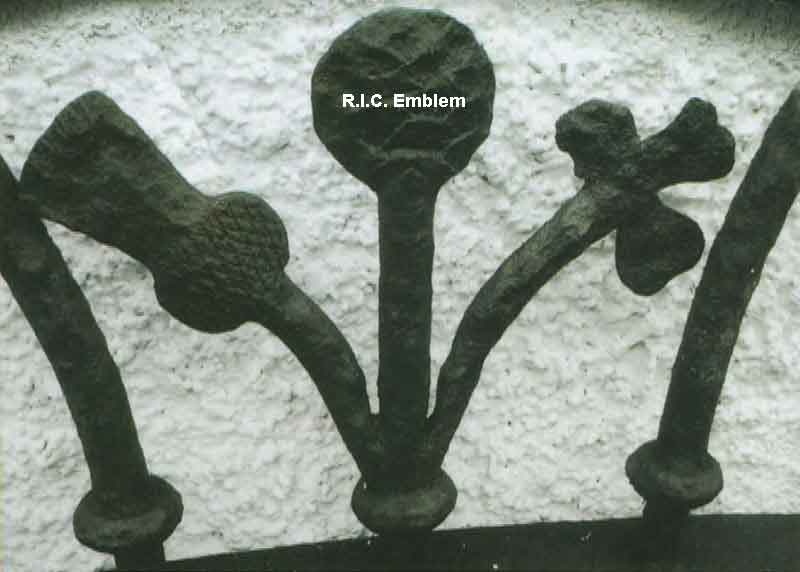

Mardyke, known locally as ‘The Found’, is the first coalmining site in Slievardagh of which we have documented/detailed information. In 1824 the Mining Company of Ireland was formed by an Act of Parliament. In 1826 the Mining Company opened extensive collieries at Mardyke, in the parish of Killenaule. The Company leased the land for 21 years from three landowners, Palliser, Tighe and Ponsonby . By July 1826 an engine house and nine dwelling houses for workers had been erected. The first steam engine (14 horse power) in Slieveardagh was introduced by Charles Langley for his colliery in Lisnamrock (Coalbrook). Mardyke village was launched in 1827 when the foundation stone, inscribed with the legend ‘industry, integrity and perseverance’, was inserted in a wall in front of the office/overseer’s house. A further 16 houses were constructed by 1832 and in 1848 Mardyke had a complement of 33 houses in three streets- New Street, (Also called Puddle St) Middle Street and High Street. In 1841 there was a temperance hall, a saving’s society and a lending library, a Primary School and a Royal Irish Constabularly Barracks in the settlement. One of the Mardyke steam engines, probably that housed in the building whose shell has survived, cost £2,500 and was brought from Waterford along the Suir to Clonmel and hauled by road from there. A thick ‘bob wall’ supported a massive cast iron beam which was rocked by the action of the steam engine under one side. The rise and fall of the opposite side provided the power to the pumps deep in the engine pit in front of the building. The adjacent chimney (locally referred to as a steeple) dispersed the smoke. All of the wood and metal components of the engine, with the exception of one cylinder bolt, have long since disappeared.

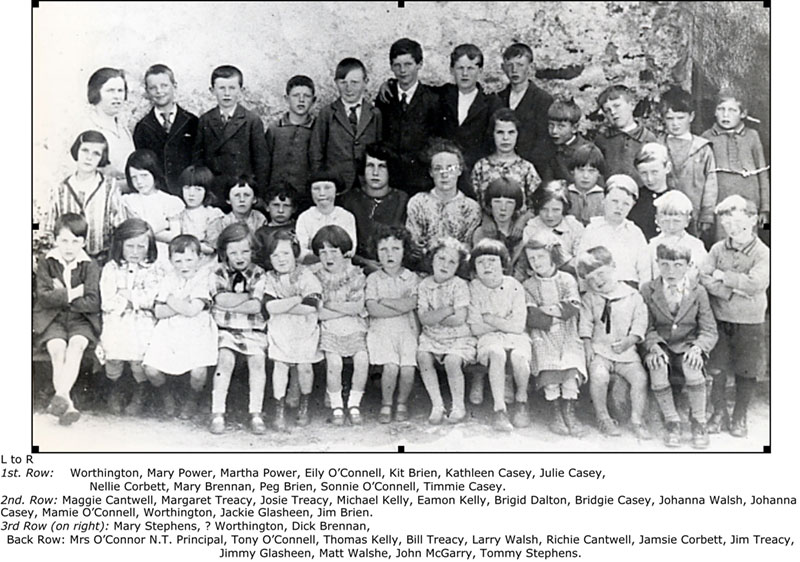

School Photo taken in 1929…….

Mardyke was one of the earliest planned industrial villages in Ireland and, although mining ceased in the 1840s, workers in the new mines at Earlshill and Blackcommon (The Commons) continued to live here. One of its residents, mining engineer John Pemberty, gave evidence at the state trials in 1848 of meeting William Smith O’Brien and his revolutionary companions as he (Pemberty) travelled to work in Blackcommon in July 1848. Little now remains apart from the school, an engine house shell, an almost perfect chimney, foundations of another engine house, the overseer’s house/office and a solitary ruined workman’s house.

At this time a steam engine was providing power for the workings and the company built an engine house and 9 dwellings for workmen. In 1829, 10 additional houses were built for workers. In 1831 the lease was extended for 41 years and in 1832, 6 more houses were built for the miners. Offices, a police barracks and a school were also built and Mardyke became the first mining village in Ireland.

When driving through the area tall chimney like structures can be seen, these steeples were used as ventilation shafts for the larger operations, (by lighting a fire in the chimney a draught was created which pulled the impure air from the mine shaft below). These chimneys were built at Lisnamrock, Earlshill, Mardyke, Foilacamin, Newpark, Boulea and Copper. (Mardyke, Lisnamrock, Earlshill and Copper are still standing). Some of the big landowners in the area were also mine-owners and when farming became less profitable they developed the mining end of their business. These included Barker of Kilcooley, Charles Langley of Coalbrook, Ambrose Going of Ballyphilip, Sir Vere Hunt of Glengoole. At this time the Slieveardagh Mining Company were in existence based at New Birmingham (another name for Glengoole). This was a small company and was having trouble keeping its head above water. Problems included the local geology where seams were inclined to fault and vanish, the tendency of mines to become flooded, and the fact that coal was expensive to transport beyond the local coalfields.

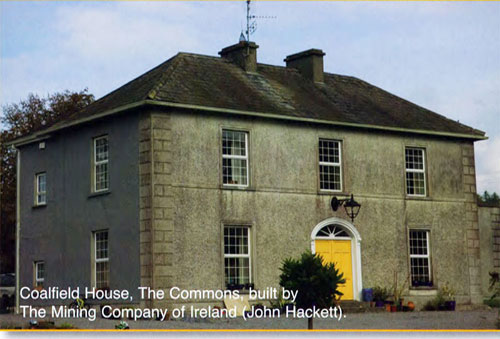

Large scale mining began in The Commons between 1839, when the map shows a police barracks, and 1848, when witnesess at the trials of the Young lrelanders referred to mining operations here. The mining remains at The Commons consist of the original row of houses with an archway under one of them which gave access to the pithead and associated yards. Two pits -Ballady and Glasgow- are still open and the ruins of the office/stores are located north of the village.In the 1850s the Mining Company erected two more substantial houses

Slieveardagh House and Coalfield House for its managers, Cullen and Lamphier. Maps also show three engine houses in Clashduff townland, north of Venter Fair House, in 1839 but all had disappeared by 1903.

Five dwellings were built in the townland of Blackcommon. They were occupied by the families:- Owen Cullins, John Lamphier, Kieran Leahy, James Kelly and James McEvoy. A School was built by the Company in Kyle Lane about 1826 and lasted until the old two story building was constructed in 1887.

.

During the Famine years the Company was mining at a loss, the miners were kept in employment. Production recorded for the years 1843 to 1853 totals 51,787 Tonnes Coal and 284,019 Tonnes duff (culm). Apart from mining and farming there were few other ways of making a living in this remote, hilly district . A decline in coal mining came around 1900 and mining almost completely ceased in 1919, apparently because explosives could not be obtained. Locals however continued to sink shafts called ‘bassets’, the landowner getting a percentage of the profit and free coal. Mr. William Young worked 1.07 acres in the Lickfinn and Glengoole South areas around this time and is recorded as recovering 3,200 tons.

During the Famine years the Company was mining at a loss, the miners were kept in employment. Production recorded for the years 1843 to 1853 totals 51,787 Tonnes Coal and 284,019 Tonnes duff (culm). Apart from mining and farming there were few other ways of making a living in this remote, hilly district . A decline in coal mining came around 1900 and mining almost completely ceased in 1919, apparently because explosives could not be obtained. Locals however continued to sink shafts called ‘bassets’, the landowner getting a percentage of the profit and free coal. Mr. William Young worked 1.07 acres in the Lickfinn and Glengoole South areas around this time and is recorded as recovering 3,200 tons.

The Mining Company brought a steam engine here in 1830 and two more from abandoned workings in Roscommon and West Cork in 1832. In 1837 there were eight pumping engines operating in the 34 working mines in the Slieveardagh Coalfield.

.

An extraordinary letter was addressed to The Mining Company of Ireland by William Smith O’Brien, the Young lrelander, in the early morning of 29 July 1848. O’Brien,anxious to improve the conditions of the miners who supported him,advised the Company to reduce the price of coal and culm and to apply all income from sales to the support of the workforce during the economic crisis brought on by the Famine. He concluded his letter with the following statement: “In case he should find the Mining Company endeavours to distress the people by withholding wages and other means, Mr. O’Brien will instruct the colliers to occupy and work the mines on their own account; and in case the Irish Revolution should succeed, the property of the Mining Company will be confiscated as national property”.

An extraordinary letter was addressed to The Mining Company of Ireland by William Smith O’Brien, the Young lrelander, in the early morning of 29 July 1848. O’Brien,anxious to improve the conditions of the miners who supported him,advised the Company to reduce the price of coal and culm and to apply all income from sales to the support of the workforce during the economic crisis brought on by the Famine. He concluded his letter with the following statement: “In case he should find the Mining Company endeavours to distress the people by withholding wages and other means, Mr. O’Brien will instruct the colliers to occupy and work the mines on their own account; and in case the Irish Revolution should succeed, the property of the Mining Company will be confiscated as national property”.

The Mining Company of Ireland was wound up in 24 July 1886 and The Commons and other sites were worked in the 1890s under the direction of local men such as Patrick O’Connor and Patrick McCormack.