Ballintogher and Kilboy

The Settlement and Architecture of Later Medieval – Slieveardagh, County Tipperary. Richard Clutterbuck – Volume II

This thesis is presented in fulfilment of the regulations for the degree of M.Uttin Archaeology, University College Dublin. – Supervisors: Prof. Barry Raftery, Dr. Tadhg O’Keeffe, Dr. Muiris 0’Sullivan, August 1998, Ballinalacken Church, Glengoole South Td., Kilcooly Pr. 48/l6, S 242 508, Tl 048-0420 I, 10/1997

Ballintogher Church & Kilboy Holy Well (alias Perry’s Well),

BaIIintogher Td., Graystown Pr.

54/6, S 156457 (Church); S 203-462 (Well House)., T1054-00901 (BaIIintogher Church); TI054-03801 (Kilboy Holy Well), 11/1997,8/3/1998

Location: Ballintogher church is situated in the south west of the study area on the top of a hill called Church Hill (Fig. 32). This is part of the escarpment and overlooks northern lowlands and bogs to the north and the hills to the east and south. The site is l.lkm north by north-east of Graystown and 824 metres north, north-west up hill from Kilboy Holy Well. Ballintogher church is sited at an altitude of 170 metres on the crest of a prominent hill. There appears to have been a path from Laffan’ s hridge in the east to the church but now the site is reached through the fields from a road 200 metres the north of the site.

History: Ballintogher church does not appear in the medieval historical documents nor is it depicted in the Down Survey parish map. The church of Ballintogher appears to have been a private chapel in a relatively isolated part of Slieveardagh.

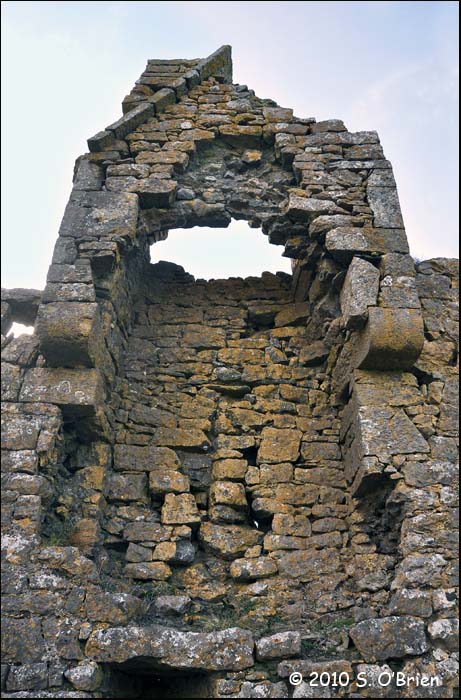

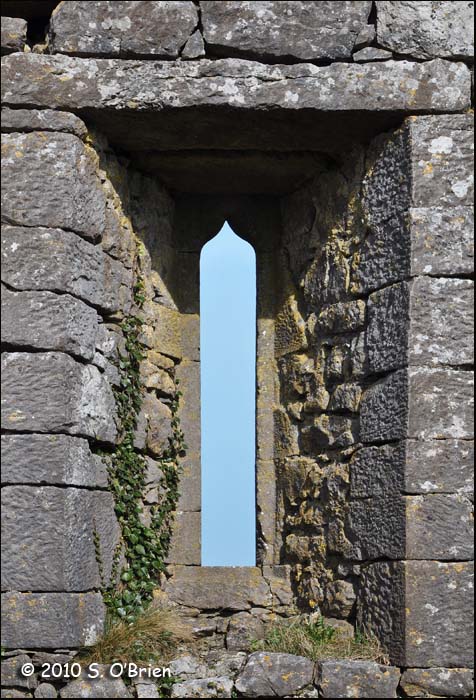

Description: Ballintogher church is a simple rectangular building constructed of roughly coursed dressed limestone blocks with a base batter. The church measures externally 11.9 metres by 6.85 metres excluding the base batter and has a width-to-length ratio of 1.7: 1. The south wall survives to a height of approximately 1 metres. The gables and north wall are still largely intact. The church was entered through a pointed arch door in the north wall. The door was executed in limestone with multiple orders of which only the bottom courses of the jambs are still in place. The rest of the door frame lies in fragments around the outside of the entrance. The interior of the church had an undifferentiated nave and chancel. The surface of the walls are hammer-dressed limestone; the interior was originally heen covered in harling or plaster. The interior was lit by at least two windows surviving on the east and west gables. There may have been windows on the south wall but have been destroyed by the collapse of the upper portion of the wall. The east window is a narrow tall chancel light with an ogee-head set in splayed ingoings. The off-centre west window is a narrow small slit light with deeply splayed ingoings.

There was a wall cupboard in the south-east comer of the church which served as an aumbry. This now breaches the wall due to the quarrying of stone from the outside. There is also a breach in the north-east comer of the church. The altar was beneath the east light and spanned three quarters the length of the east wall from the north east corner. The remains of the altar can be seen as a recesses in the east wall and the lower courses of the front of the altar parallel to this. The west gable has the remains of a bellcote set over the west window. The bellcote was built into the gable as a recess and was housed in a corbelled projection at the top of the gable with the ropes hanging into the interior of the church. The bottom quoins at the corners of the church have been removed, destabilizing the walls.

The Ordnance Survey Letters record the presence of a carved effigy in limestone of the Madonna and Child outside the door of the church. (0. S Letters Co. Tipp., 199). This can now be found at Kilboy holy well 665 metres south-west downhill from the Ballintogher church.

A semi-circular earthwork to the north of the church and the lower course of a wall attached to the north east corner of the church appear to be the remains of an enclosing stone wall in front of the church entrance. There are the remains of at least five houses surrounding the church to the north, west and south. These appear on the ground as platforms of sub-rectangular earthworks and are the remains of a settlement associated with the church. The land to the north of the church has been quarried, possibly removing more evidence of the settlement.

Comment: This is a small late medieval church built in a very exposed site on the top of a hill. It has a commanding view over the lower lying lands to the north and west and over the hills to the south and east; the church stands out as a landmark. The design of Ballintogher church and its width to length ratio are similar to other late medieval chapel churches in Slieveardagh like Mellisson (44) and Knockanglass (38). The quality of the stone work is superior to other churches of this nature in the barony. The church appears to have been a private chapel but also had an associated settlement which in such an exposed and isolated location may suggest a religious community.

Kilboy Holy Well-House (locally known as Perrys Well)

Perry’s Well: – local legend says the well was originally up at Church Hill, about 1.5 km away, until someone washed sheepskins in it.

Location: Kilboy holy well-house is situated 824 metres south by south-east of Ballintogher church. (S 203-462). Kilboy holy well is sited at an altitude of 160 metres beside a small stream.

Entrance to the Well with Maura Barrett in focus, – photo courtesy of Sean O’Brien

Description: Kilboy holy well is contained within a rectangular stone vaulted structure constructed of limestone with sandstone sill stone and surrounds for the original entrance. The well-house has recently been ‘restored’ by private initiative and is now encased in concrete and pebble dash (Plate 7). The original structure measured 5.37 metres by 3.3 metres. The well house was originally entered through a door in the east corner of the north wall. The structure is now entered through a modem second entrance in the original east gable. The interior of the well house is lit by a single slit window in the west gable. A central trough of water runs along the centre of the interior where the spring rises and flows out the new entrance. The sides of this trough allowed people to sit and dip their feet in the water. The water in the trough is extremely clean with a bedding of fine sand (Hemphill 1912, 328). The bluntly pointed vault ceiling has the impression of wicker centring. The ceiling and roof were in excellent condition in 1912, however, half the ceiling had subsequently been replaced with concrete during the recent work. The site roof was overgrown in 1912 and had a special chair for pilgrims who were required to sit on the roof (Hemphill 1912, 326). The site has a Pieta of a defaced Blessed Virgin Mary holding the Dead Saviour in Her lap. Hemphill (1912) described this as leaning against the wall of the well-house; it now lies in the grass.

As far back as the 1960s, a small cast-iron figure about 12inches tall could be found near the well, where ‘votive offerings’ were left. I brought Dr. Etienne Rynne of the National Museum in Dublin to see the place. He said the figure appeared to be of Spanish origin. The figure is no longer visible around the area. At that time in 2010, when we had cleaned up the artifacts, the County Archaeological Officer and the National Museum were notified by Maura Wall-Barrett and photographs sent to them. They visited the site and appeared to be quite interested, but nothing seems to have happened since. – photo and caption courtesy of Sean O’Brien

The ‘Kilboy Dancers’ – a title I coined myself – located at a nearby stile, after cleaning up. Photo courtesy of Sean O’Brien

Cathaganstown Castle Site,

Cathaganstown Td., Killenaule Pr., 54/14, S 196442, Tl054-49, 11/1997Location Cathaganstown townland is situated in the south of the study area on the slopes of the Calshawley river valley (Fig. 32). The land quality is good duel purpose arable and pasture. In relation to other sites, Cathaganstown castle was 1.75km south of Graystown (27), 3.4km south-west of Killenaule (37) and 1.9km north, north-west of Knockanglasse church (38). Cathaganstown castle was sited at an altitude of 160 metres and built on the side of the hill sloping to the Clashawley river. The site had a west and southerly aspect, down the Clashawley river valley. It was sheltered by the rest of the hill to the east and was well light. The Clashawley river flows approximately 700 metres downhill to the west of the site. The site was adjacent to the road running east, uphill out of the river valley.

Historical: The townland was owned by Theobald Mansell of Cathaganstown in 1641 (Civil Survey I, 109).A castle is not recorded in Cathaganstown in the Civil Survey or Down Survey. The Ordnance Survey recorded that the site of the castle was used as an inn (O.S. Letters Co. Tipperary, 125).

Description Cathaganstown castle has been totally destroyed and is recorded as a site only in the 6″ maps ( OS Tipperary Sheet 54). The proprietor of this townland in the seventeenth century was Theobald Mansell who presumably lived in the castle.

Comment Cathaganstown castle does not appear in the historical record but was probably a tower house. Alternatively it may have been a planters defended house like Graiguepadeen castle (m.6) in the north of the study area.

Comment: Kilboy holy well appears to have been the site of pilgrimage in the nineteenth century though the practice had died out by 1912 (Hemphill 1912, 325- 326). The design of the building points to a later medieval date. The Pieta was originally sited at Ballintogher church where it is described in the Orduance Survey (O.S. Letters Co. Tipperary II, 199; Hemphill 1912, 330). It may not be a coincidence that a member of the O’Tunney family (sculptors from Callan County Kilkenny who carved the effigy of Pierce Fitz age Butler in Kilcooly abbey 1526) rented land in Ballintogher townland in the sixteenth century in 1596 (arm. Deeds VI, 86) though this is after the floret of the work shops activity which spanned from the mid-fifteenth century to the mid-sixteenth century.