David Power Conyngham

FROM BALLINGARRY TO FREDERICKSBURG:

DAVID POWER CONYNGHAM (1825-1883)

By Michael Fitzgerald

The subject of this article achieved distinction in several fields; yet today it is rare to find Tipperary people who know of him. He was a patriot and a revolutionary in 1848, a novelist and historian and a journalist on America’s greatest newspaper in his time.

He saw action as an officer in the American Civil War, where he was wounded in action and commended for bravery. He remained an uncompromising patriot all his life. He was a cousin and friend of Charles Kickham, a friend and admirer of Meagher of the Sword and a friend of John O’Mahony and other leading Fenians.

David Power Conyngham was born in Crohane, near Killenaule County Tipperary, in 1825. The exact date of his birth cannot be traced because the baptismal registers for Ballingarry parish for that year are incomplete although records exist for most other members of his family. However, most reliable accounts give the year 1825, and agree that he was three years older than Kickham.

He was the eldest son of John Cunningham and his wife Catherine Power. His parents were well-off farmers. In the Griffith Valuation lists John Cunningham is shown as a tenant of over 142 acres, held in 1855 from Malcolmson, Pike and Fennell. In addition, he held several small holdings which were sublet to others, the largest to a William Cunningham, who may have been a brother or other close relative. William also had a son named David, a fact which made research somewhat confusing.

Catherine Power’s mother was a Kickham according to local tradition, apparently a sister of Charles Kickham of Ballydavid, grandfather of the novelist. This tradition is supported by the fact that James Kickham of Mullinahone, uncle of the novelist, acted as baptismal sponsor for another Cunningham brother.

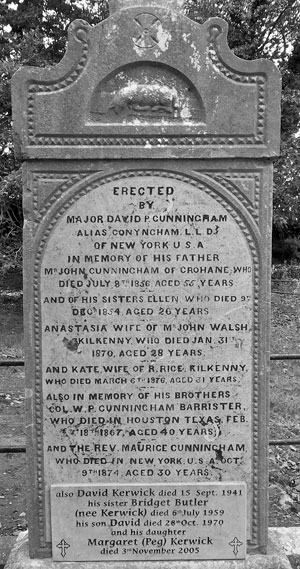

The land was the Powers’ property; John Cunningham had married in there, and his own native place is not recorded. The surname was then very common; at least half-a-dozen Cunningham families lived in Killenaule parish. Early marriages were the norm in the early nineteenth century, and if the ages on the family tombstone in Lismolin are correct, John Cunningham was only 19 when David was born.

A Thomas Power, probably an uncle, also held a substantial holding in Crohane and a Richard Power of Crohane took part in the 1848 Rising. Richard’s name appears several times in the marginal graffiti on classical textbooks used in the hedge schools in the area at the time, which seem to have attracted scholars from as far away as Ballaghadereen, county Mayo. The graffiti also mention the Mahers of Laha, Castleiney, who ran a famous classical school.

David presumably received his early education at one of these schools. Later he went to Queen’s University Cork, but left without a degree, as was quite common then. He is believed to have been intended for the priesthood, but found he had no vocation. Later his younger brother Maurice became a priest; he died in New York, aged only 30, in 1874. He and David are buried in the same grave in Calvary Cemetery, New York; a nephew Laurence also became a priest and laboured in the United States for many years.

After leaving Cork David did not settle down in any occupation. He roamed round Tipperary during those famine years, probably staying with various relatives – absorbing all he saw, listening to stories and traditions. He retained them all in his remarkable memory, and later was to use many of them. David was a frequent visitor to the home of the Kickham cousins in Mullinahone, becoming a close friend of Charles, three years his junior. They had much in common and shared political views.

David became a Young Irelander, and later a Confederate. Even at this stage he was an extremist, who saw no good, under any possible circumstances, in the British connection or the landlord system. He never changed these views. He seems to have been influenced by James Fintan Lalor and Thomas Davis in particular, although his political philosophy was probably nearest to that of John Mitchel.

From early 1848 it became gradually obvious that rebellion was coming. O’Connell was dead. Meagher and Mitchel were openly calling for insurrection. Eventually the government pounced. Mitchel was tried before a packed jury, sentenced and transported. William Smith O’Brien took over. The leaders, when warrants were issued for their arrest, left Dublin for the country. Their journey took them to Kilkenny, Waterford, Carrick-on-Suir, Mullinahone and eventually to Ballingarry.

Cunningham was deeply involved from the beginning as the leader of a Confederate Club. He is said to have acted as a guide in the area, and took part in the Council of War in Ballingarry just before the Rising. The evidence given at the trial of Smith O’Brien and the other leaders shows the extent of his involvement. After the collapse of the Rising at Farrenrory he was immediately placed on the police list of wanted men. The police sought informers, but found few of any use to them.

Members of the Unionist ascendancy usually confined their evidence to the fact that their houses had been raided for arms, naming only the raiders known to them. Others, either reluctant or simply “on the make”, mentioned only those already known to the po1ice. Their evidence was worthless, since it seldom gave evidence of treasonable intent. Only two witnesses were of use; one was an Englishman employed by the mining company, the other a summons server. Here are some extracts from their statements.

“On Wednesday, 26th of July, the chapel bells commenced ringing to join those at Mullinahone, and at the hour of ten o’clock that evening 400 persons assembled, all armed in various ways, and proceeded under the command of said McCarthy (schoolmaster at Mr. Fitzgerald’s of Jessefield), John Cormack of Boulea, David Cunningham of Crohane, and Wright of Mullinahone, with music on the way to Mullinahone. I accompanied them till we met Smith O’Brien, J.B. Dillon, a person called Donohue from Dublin, Devin Reilly and some other with about 200 persons, mostly armed, coming on to Ballingarry

I was in the village of Ballingarry on Thursday 27th of July when about noon I saw William O’Brien drilling a larg mob of persons in the street, some armed with guns and pistols, others with pikes, pitchforks, and other weapons … Mr. O’Brien also told them that he had appointed David Cunningham of Crohane also a commander, and asked them if they were satisfied to obey him whenever he called on them, on which they replied Yes. I heard David Cunningham ask the mob if they knew of any persons having arms who were not joined with them; and if so, to take them by force and to mark them. I afterwards on the same day saw the aforesaid John Cormack and David Cunningham leading the said mob who were formed four deep. Cunningham was armed with a gun.”

At the trial of Smith O’Brien and the other leaders, the evidence was similar; but the summons server was a bit worried at that stage. Under cross-examination he said he had heard of Cunningham, but did not know if he should know him or not. Later he said that on the 28th of July he saw David Cunningham and a person whom he heard was a schoolmaster at Martin Fitzgerald’s of Jessfield, drilling the people and acting as leader. He admitted he got £20 reward for his information.

The Grand Jury, whose duty it was to decide if the defendants named should be sent forward for trial, found true bills against eight of the defendants as well as the principal leaders. The eight were: Edmund Egan, John Cormack, William Peart, Thomas Finnane, David Conyngham, John Brennan, John Preston and Thomas Stack. Only seven prisoners appeared at the bar. Cunningham was missing.

The Grand Jury, whose duty it was to decide if the defendants named should be sent forward for trial, found true bills against eight of the defendants as well as the principal leaders. The eight were: Edmund Egan, John Cormack, William Peart, Thomas Finnane, David Conyngham, John Brennan, John Preston and Thomas Stack. Only seven prisoners appeared at the bar. Cunningham was missing.

Since he gave no account of how he escaped it is reasonable to assume that he escaped from custody. Normally no case went to the Grand Jury unless the accused could reasonably be expected to stand trial. There is no evidence that he was actually present at the War House, but he probably was. Many years later, in his book Ireland Past and Present he remarked that many of those who took part were sons of leading farmers, and mentioned as such, “Power’s, Kickham’s, Fitzgerald’s, Mullally’s and Cunningham’s”.

Most accounts say Cunningham escaped to the United States at this time. One writer, Rev. W. Hickey, merely states that he had to leave home, others that he went to America in 1861 or in 1863. In the shipping lists of emigrants who landed in New York in November 1848, there is a David Cunningham, aged 40, labourer. The age does not agree; Cunningham was then 23, but these lists are far from reliable in such matters.

Probably his brother William had to leave home too; David’s use of the plural above suggests that he was also involved. These were the years of the great exodus from the Famine and of the coffin ships. Thousands were fleeing the country daily, and escape in disguise was easy.

However, after a few years, he was back in Ireland, possibly because of the illness and death of his father or sister Ellen. Both died in 1856. His father had suffered considerable losses in the years before he died, as a result of the Famine and the failure of a local loan fund bank of which he was chairman.

After David’s return he began contributing literary and political articles to the Tipperary Free Press, published in Cashel. No copies containing his work appear to have survived although some, unsigned but identifiable, were reprinted in another Cashel paper in the 1880s. He probably wrote for other papers as well. His brother Thomas inherited the family farm; this may have been a family arrangement.

In 1859 his first novel was published by Duffys, Dublin entitled The Old House at Home by “A Tipperary Boy”. A new edition in 1861 was entitled Frank O’Donnell by Allen H. Clington. Several later editions under the title The O’Donnells of Glen Cottage bore his real name. This novel was still in print in 1917.

Based loosely on real events, its main theme was the judicial murder in 1858 of the Cormack brothers of Loughmore for the alleged shooting of John Ellis in 1857. It was undiluted nationalism- anti-landlord, anti-British, anti-”souper”. The sufferings of the starving people take up much of the story. The style and dialogue bear a strong resemblance to the work of Kickham. It was probably the first novel of the time to take such a strong nationalist stand.

In November 1860, according to Kickham, Cunningham was among those who welcomed home the Mullinahone contingent of the Papal Brigade. The following April the American Civil War began; he returned to the United States and joined the staff of the New York Herald.

It is by no means easy to reconstruct his movements at this time. Existing accounts vary and often contradict one another. For example, an obituary in the Tipperary Leader states he went to the United States in 1863 with letters to General Meagher from Smith O’Brien and P.J. Smyth. According to Cunningham, Fr. Hickey was there as a journalist in April 1861.

It seems certain that he joined the New York Herald in 1861, and the fact that he obtamed such a post on the country’s biggest paper suggests that he was already known there, or had previous experience in the 1848 – 1855 period. The editor was a Scot, James Gordon Bennett, who detested England and all it stood for; many of the staff were Irish, former members of Young Ireland. Conyngham, as his name was now spelt, was sent to the front as a war correspondent. As such he was attached to the newly-formed Irish Brigade.

While the 69th New York Volunteers- the “Fighting Sixty-Ninth”- is always associated in the public mind with the Irish Brigade, the fact is that the Brigade consisted of five regiments. At first these included the 63rd and 88th New York regiments; at various times during the war the 116th Pennsylvania and 28th Massachusetts regiments became part of the Brigade. At one time the 29th Massachusetts was also part of the Brigade; but this was later replaced by the 28th. MEAGHERS REGIMENT THE FIGHTING 69th.

MEAGHERS REGIMENT THE FIGHTING 69th.

Conyngham seems to have been a civilian war correspondent in the early years of the war. His name does not appear on any list of officers before March 1863, when he was a captain and acting aide-de-camp to General Meagher at the battle of Chancellorsville. He was then a staff captain, attached to the Brigade as a whole rather than to any individual regiment. It is likely that he had held this rank for some months before that.

Conjecturally, from various pieces of evidence and from a close examination of his book The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns it is possible to check at least some of his movements. Using this method it appears he was not at the front in the early months of 1861, after the war started. From September the narrative shows a more personal tone than when it described the first months. These appear to have been written from newspaper reports, in particular those of a James Turner. Then Conyngham was with the Brigade until about Christmas of that year, when he returned to Ireland.

In February of 1862 he married in Killenaule Anne Corcoran. The marriage was not a success;· the reasons are not recorded, but a tradition I have heard suggests that both parties may have been at fault, and it is likely that his return to the States had a bearing on the rift. It seems that his later returns to this country in the next ten years were connected with attempts to heal the rift. He was in his 37th year then, and his bride a few years younger. She also came of comfortable farming stock.

The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns shows for most of 1862 the same features as it did in early 186l.lt was written from the reports of others. Then he returned, probably before Christmas 1862, when the narrative takes on a more personal note. It was most likely on this occasion that he brought letters to General Meagher from P.J. Smyth and Smith O’Brien, and was appointed a staff captain to the Brigade.

He also continued to send reports in his capacity as a war correspondent. According to his obituary in the Tipperary Leader this occurred in 1863, when the Brigade was encamped before Fredericksburg. In fact the brigade was encamped there in November 1862, and the battle there took place on 13 December 1862.

The issue which caused the American Civil War was not slavery, but whether individual states had (or had not) the right to secede from the Union. The Irish were divided on this. Before the war Meagher had favoured the southern view. Mitchel remained a Confederate to the end, making himself very unpopular in New York, a city of which his son later became Mayor.

The Cunningham family was also divided. David’s younger brother, William, who had also fled after the ’48 Rising, had gone at first to Canada.

The Fighting 69th Insignia

Later he moved south to Houston in Texas, where he established a very successful law practice, and joined on the Confederate side. William had married a native American from Carolina, had no children of his own, but had two adopted daughters- possibly step-daughters if his wife Sarah had been married before.

William joined the Second Texas Infantry in or before August 1861as a second Lieutenant. His later war history is not recorded, but it is known that he reached the rank of Colonel. Possibly he was the Colonel Cunningham who served under Stonewell Jackson at the battle of Gaines Mill in 1862.

We know from David’s own account that David twice crossed the lines secretly and in civil dress, hoping to meet someone who might have news of him. I have heard one story from tradition that, after the capture of a Confederate town, David was challenged in a saloon by a man who told him that he had seen him in the same saloon a week before wearing a Confederate uniform. There was a strong family likeness between the brothers.

David Conyngham was a modest man, who rarely mentioned his own doings. As staff officer and aide-de-camp he was close to General Meagher and in a position of danger. Meagher was brave to the point of recklessness and on one occasion he had his clothing in tatters from bullets nd his horse shot, refusing to move his command post until the last moment. Conyngham himself had four horses shot under him, was wounded in the breast at the battle of Resaca, mentioned in despatches and commended for bravery.

Of all the battles in which the brigade took part, that of Fredericksburg was by far the bloodiest for the brigade itself. The town of Fredericksburg was of vital strategic importance. Here on 13 December 1862 the Brigade was ordered into action against the Confederates, who held a virtually impregnable position behind stone wall embankments on a hill called Maryes Heights.

Before the battle Meagher gave out green sprigs of boxwood to all ranks for their caps, to identify them as Irish. Zookes Brigade led the uphill charge against Maryes Heights against a withering fire, which quickly thinned their ranks. Meagher’s came next. The artillery could give no support; there was almost no cover, and the advance was impeded by piles of bodies. Two-thirds of the brigade were lost.

Conyngham commented: “It was not a battle. It was a wholesale slaughter of human beings – THE END

December 24, 1861: The Irish Brigade celebrates Christmas

From “The Irish brigade and its campaigns” by Captain David Power Conyngham:

“It is no wonder that most of the regiment were gathered around there, for it was Christmas Eve, and home-thoughts and home-longings were crowding on them; and old scenes and fancies would arise with sad and loving memories, until the heart grew weary, and even the truest and tenderest longed for home associations this blessed Christmas Eve.

No wonder if amidst such scenes, the soldier’s thought fled back to his home, to his loved wife, to the kisses of his darling child, to the fond Christmas greeting of his parents, brothers, sisters, friends, until his eyes were dimmed with the dews of the heart. The exile feels a longing desire, particularly at Christmas times, for the pleasant, genial firesides and loving hearts of home. How many of that group will, ere another Christmas comes round, sleep in a bloody and nameless grave I Generous and kind hands may smooth the dying soldier’s couch ; or he may linger for days, tortured by thirst and pain, his festering wounds creeping with maggots, his tongue swollen, and a fierce fever festering up his body as he lies out on that dreary battlefield; or, perhaps, he has dragged himself beneath the shade of some pine to die by inches, where no eye but God’s and his pitying angels’ shall see him, where no human aid can succor him. Years afterwards, some wayfarer may discover a skeleton with the remains of a knapsack under the skull. This is too often the end of the soldier’s dreams of glory, and all

“The pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war.”

It is but a short transition from love, and hope, and life, to sorrow and death.

Another Christmas, and many a New England cottage, and many a home along the Rhine and the Shannon, will be steeped in affliction for the loving friends who have laid their bones on the battlefields of Virginia.

If any indulged in such reflections, the lively tones of Johnny O’Flaherty’s fiddle, and the noisy squeaks of his father’s bagpipes, soon called forth the joyous, frolicksome nature of the Celt.

Groups were dancing, around the fire, jigs, reels, and doubles.

Even the colored servants had collected in a little group by themselves, and while some timed the music by slapping their hands on their knees, others were capering and whirling around in the most grotesque manner, showing their white teeth, as they grinned their delight, or ” yah-yahed,” at the boisterous fun.

The dance is enlivened by laugh, song, story, and music; and the canteen, filled with wretched “commissary” goes freely around, for the men wish to observe Christmas-times right freely.

“Arrah musha, Johnny O’Flaherty, sthop that fiddle and take a drink, alanna,” said a why red-haired man, with a strong Kerry accent. ” Do, Johnny,” said the father, who had taken a long pull at the canteen himself, and now proffered it to his son.

“It is as well to keep up our spirits by pouring spirits down, for sure there’s no knowing where well be this night twelvemonth,” exclaimed another of the group, as with a sigh he comforted himself from his canteen.

“Thrue for you. Bill Dooley; shure myself thinks that our rations will be mighty short again another Christmas comes round,” said a little cynic, who was pulling very hard at a dudeen.

“Begor then, Jem, maybe they would be long enough for us.” .

“Well, boys, long or short we won’t disgrace the poor ould dart, any way.”

“Bravo, Mannigan, bravo! you said the truth in that.”

“Bad scran if I can see what the ould dart (Ireland) has to do with it at all, at all,” replied the cynic, as he knocked the ashes out of his pipe against the log.

“Oh, dear me! do ye hear that? and would you disgrace it?” exclaimed an indignant patriot.

“And shure won’t they be lookin’ at us at home, to see how we’ll fight?” said another.

“An’ I’d rather be in my grave, any day, than have it said that I was a coward,” said a young fellow, slapping his hand forcibly on his thigh.

“Well, that’s all very fine,” said the cynic, who, seeing the force of evidence against him, was fain to recant ; “but, boys, if we were fighting for the poor ould dart, wonldn’t it be glorious?”

“Bad luck to you, Jeff Davis, any way ; only for you we’d be at home, comfortable and happy, with the girls, this blessed Christmas Eve!” exclaimed a lovesick youth.

How often in the lull of battle have I heard the Irish soldier, begrimed with powder, as he grasped his comrades’ hands, exclaim, “What harm, if it were for the poor old dart ?”

How is it that the Government of England is blind to the ruin that a people so numerous and powerful in foreign countries, and hating her so intensely, is sure to bring on her in her hour of trouble ?

It might be politic to try conciliation, instead of coercion, on such a people.

The dance was followed by songs; and those soft, impassioned Irish airs, “The girl I left behind me,” and “Home, Sweet Home,” flowed sweetly and softly from hearts that felt their full force ; but as the strong political songs of “The Rapparee,” and “The Green above the Red,” and “Fontenoy,” were chorused by a hundred throats, that dark group of soldiers, scattered around the fire, looked as if ready to grasp their muskets and rush on some hidden foe.

These innocent and exciting revels continued until the tinkle of a small bell from a rustic chapel suddenly hushed the boisterous mirth, and all arose, reverentially doffed their hats, and proceeded to the chapel.

Fathers Willett and Dillon were going to celebrate the midnight Mass. The chapel tents were as well decorated as circumstances would allow. In front of the open tent in which the priest officiated were rude benches of hewn logs, sheltered on each side and overhead by boughs of trees, supported by poles.

The chapel was situated on the brow of a hill, and tall cedars and pines flung their sheltering arms over it.

Father Dillon was chanting a Low Mass, the responses being made by Quartermaster Haverty and Captain O’Sullivan, while the attentive audience crowded the small chapel, and were kneeling outside on the damp ground under the cold night-air.

Father Dillon read the beautiful gospel from Saint Luke, giving an account of the joumeyings of Joseph and Mary, and the birth of the infant Saviour in the manger at Bethlehem ; after which his hearers quietly retired to their tents.

The weather in camp wafi fine, almost resembling an Indian-summer. A slight frost at night and a shower of soft snow were the only indications of winter.

In Virginia, the weather at this season is generally mild and balmy, with little of the heavy frost and angry storms that rage at the North.

Such was Christmas morning, 1861, in the camp of the Irish Brigade, where willing hearts piously welcomed this holy festival, laden with the richest freight of happy recollections.

NOVELS

The O’Donnells of Glen Cottage

Sarsfield, or the Last Great Struggle for Ireland.

O’Mahony, Chief of the Comeraghs. Rose Parnell, the Flower of Avondale

CIVIL WAR BOOKS

The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns

Sherman’s March through the South.

The Sisters of Charity on Southern Battlefields

IRISH HISTORY

Lives of the Irish Saints Lives of the Irish Martyrs. Ireland Past and Present.

An Ecclesiastical History of Ireland (with Rev. T. Walsh).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amongst those who supplied information are the following:-

Michael Kerwick, Newpark, The Commons, Cashel, and James Kerwick, Ballytarsna, Cashel (grand nephews of Conyngham);

The late Thomas Walsh, The Islands, Mullinahone;

the late Mrs. Gaynor, Thurles and her sons William and Noel;

Mr. James Jordan, Dublin (on the Irish Brigades);

Mr. Michael Moroney, B. Ed., of Ballynennan, Drangan (various U.S. sources); Dr. Thomas McGrath, The Park, Ballingarry, and U.C.D.;

Professor J. McCormack, Pennysylvania State Education Association; Dr. Robert Krick, U.S. National Park Service;

Ms. Doris Glasser, of Houston Public Library (data on William P. Cunningham); Thomas Noone, Thurles (R.C. Parochial registers);

Prof. S. Pender U.C.C.

The author also wishes to thank the following institutions: The County Library, Thurles;

The National Library of Ireland; The State Paper Office, Dublin;

U.S. National Archives, Washington D.C. Catholic University of America, Washington D.C.

The following were also consulted:

Rev. W. Hickey (Leeds); The trial of Smith O’Brien in the Irish Book Lauer, January 1914;

The Tipperary Star, 1937 and 1948;

Rev. S. Brown, S.J.; Ireland in Fiction (1915);

J.J. Healy: The Life and Times of Charles Kickham (1915);

R.J. Kelly: Charles Joseph Kickham, Patriot & Poet (1914);

R.V. Comerford: Charles J. Kickham (1979);

James Maher: The Valley of Slieuenamon (Mullinahone, 1941) and Romantic Slieuenamon (Mullinahone, 1954).