The Irish Brigades

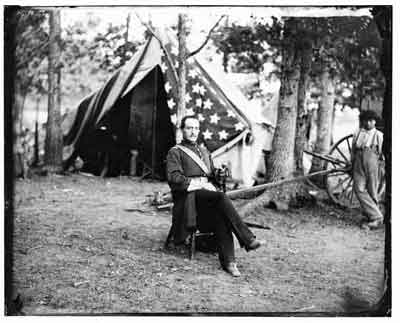

The Irish Born Commanders David Power Conyngham (photo left) born Crohane, Killenaule Thurles, Co. Tipperary 1825-1883; was a cousin of Charles Kickham: Involved in the Young Ireland Rising of 1848, and US Civil War; He took up Journalism, after US Civil War; Army Major, He wrote many works on Irish and American subjects. novels published in Boston and NY incl. Sarsfield (1871), and The O’Mahoney, Chief of the Comeraghs (1879) was following Sherman’s advance towards Atlanta as a correspondent for the New York Herald and for a time as a member of Brigadier-General Henry M. Judah’s staff. He had previously spent time as a volunteer aide with the Irish Brigade, and after the conflict would pen the most famous account of that unit, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns. He also recorded his experiences with Sherman, in his 1865 book Sherman’s March through the South. Conyngham credits Sherman himself with directing the fire on the Confederate officers which led to Polk’s death. The Tipperary man later saw the spot whereMajor Polk fell, and describes the activity that he and others engaged in at the site:

The Irish Born Commanders David Power Conyngham (photo left) born Crohane, Killenaule Thurles, Co. Tipperary 1825-1883; was a cousin of Charles Kickham: Involved in the Young Ireland Rising of 1848, and US Civil War; He took up Journalism, after US Civil War; Army Major, He wrote many works on Irish and American subjects. novels published in Boston and NY incl. Sarsfield (1871), and The O’Mahoney, Chief of the Comeraghs (1879) was following Sherman’s advance towards Atlanta as a correspondent for the New York Herald and for a time as a member of Brigadier-General Henry M. Judah’s staff. He had previously spent time as a volunteer aide with the Irish Brigade, and after the conflict would pen the most famous account of that unit, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns. He also recorded his experiences with Sherman, in his 1865 book Sherman’s March through the South. Conyngham credits Sherman himself with directing the fire on the Confederate officers which led to Polk’s death. The Tipperary man later saw the spot whereMajor Polk fell, and describes the activity that he and others engaged in at the site:

He writes ‘When we took that hill [Pine Mountain], two artillerists, who had concealed themselves until we had come up, and then came within our lines, showed us where his [Polk’s] body lay after being hit. There was one pool of clotted gore there, as if an animal had been bled. The shell had passed through his body from the left side, tearing the limbs and body to pieces. Doctor M—- and myself searched that mass of blood, and discovering pieces of the ribs and arm bones, which we kept as souvenirs. The men dipped their handkerchiefs in it too, whether as a sacred relic, or to remind them of a traitor, I do not know.’

He writes ‘When we took that hill [Pine Mountain], two artillerists, who had concealed themselves until we had come up, and then came within our lines, showed us where his [Polk’s] body lay after being hit. There was one pool of clotted gore there, as if an animal had been bled. The shell had passed through his body from the left side, tearing the limbs and body to pieces. Doctor M—- and myself searched that mass of blood, and discovering pieces of the ribs and arm bones, which we kept as souvenirs. The men dipped their handkerchiefs in it too, whether as a sacred relic, or to remind them of a traitor, I do not know.’

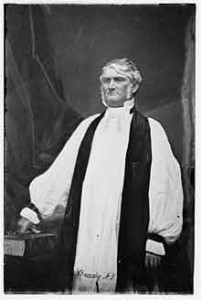

Conyngham’s is a fascinating account of the supposed actions of Union soldiers at the site where Major Leonidas Polk (April 10, 1806 – June 14, 1864 (Photo on the right) commanding the confederate Brigade died. The idea of keeping fragmented parts of the body as souvenirs and dipping handkerchiefs in the blood of their fallen enemy is one I have not come across before- have any reader’s encountered any similar accounts from the Civil War?

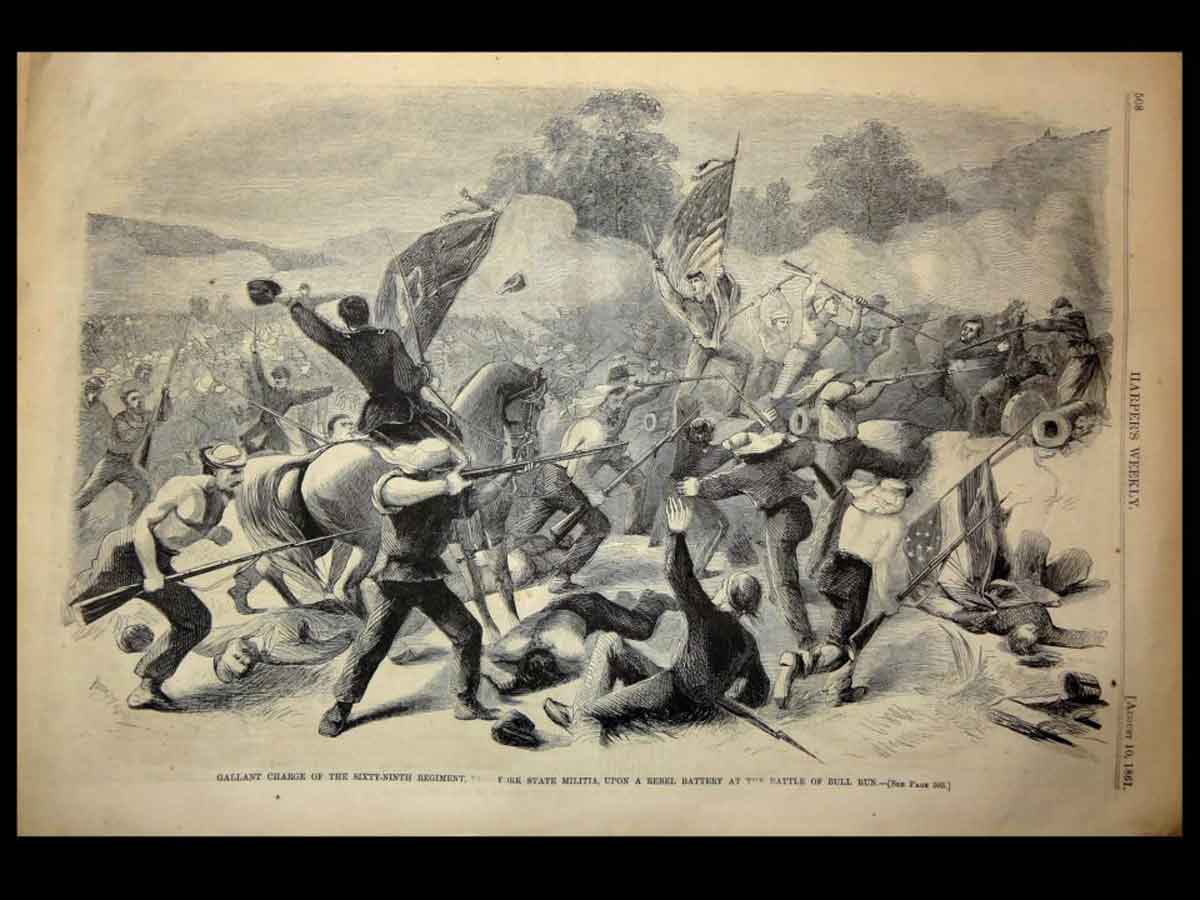

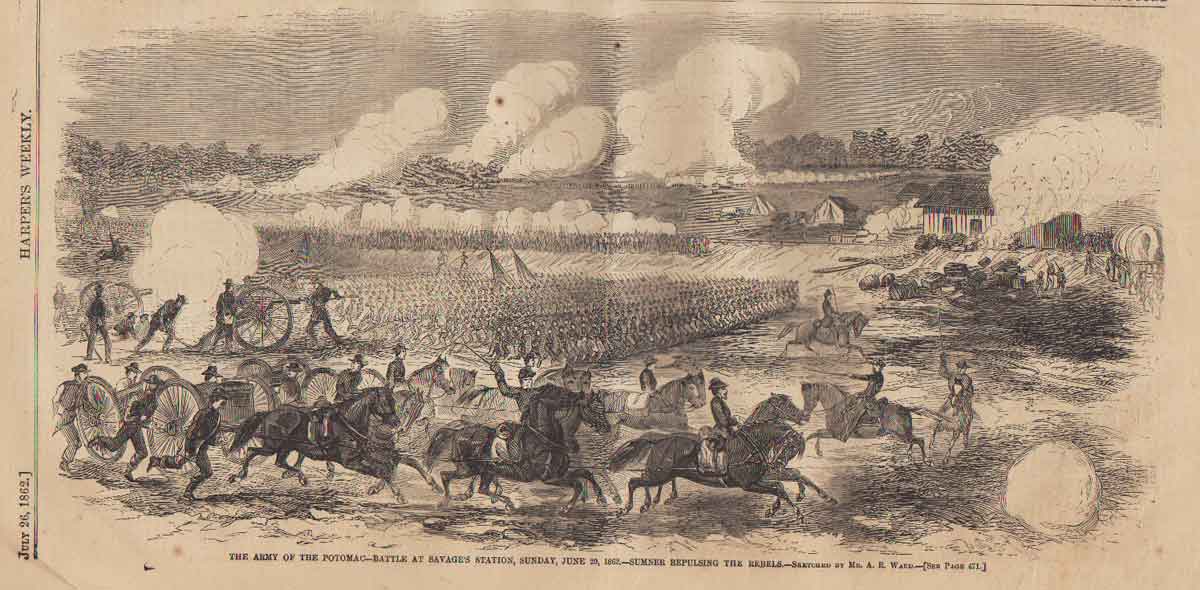

Irish Brigade and its Campaigns (1866). … with some account of [Col. Michael] Corcoran’s legion, and sketches of the Principal officers, Cpt. D. P Conyngham, author of Frank O’Donnell; Sherman’s March, etc (Glasgow). ‘Took pride tracing their progenitors to some old Celtic stock. It is only those who ‘have left their country for their country’s good’ that are low and snobbish enough to deny their native country. No true man denies his country.’. The author served with Sherman in Georgia. Meagher’s Zouaves at Bull Run; his horse killed under him; Irish Brigade evolved from New York State Militia 69th; draws link with ‘flower of Jacobite Army’ in continental service; at Fontenoy Louis publically thanked the brigade and created Count Lally a general on the field of battle; King George said, ‘Cursed be the laws that deprived me of such subjects.’ Generals in Union service, John Logan, Geary and Burney; Sweeney, Lalor, Doherty, Gorman, Magennis, Sullivan, Reilly, Mulligan, Stevenson, Meagher, Minty, Shields, Corcoran, PH Jones, Kiernan. ‘The Irish soldier did not ask whether the coloured race were better off as bondsmen or freedmen; he was not going to fight for an abstract idea. He felt that the safety and welfare of his adopted country and its glorious constitution were imperilled; … the Irish soldier was therefore a patriot not a mercenary.’ [Copy held in Belfast Central Library.]

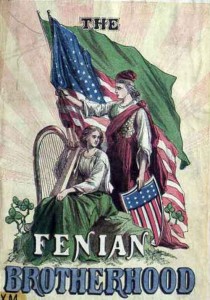

Nationalism by definition is: loving ones country and wanting to be governed by ones own people. During the second part of the nineteenth century, there was an increased progression of nationalistic feeling in Ireland. Due to this feeling there was a rise in physical force revolutionary groups, the largest organized group being the Fenians. Even though the Fenians started out in Ireland, they also established roots in America, by recruiting large numbers of the new Irish immigrant population. This was easily done due to the fact that the new Irish blamed the English for having to leave their homes in the old country. (1) The Fenian movment was at the height of popularity when the American Civil War broke out. So their ranks decided that fighting in this war would boost the movement as well as being great practice for the eventual uprising in Ireland. Even those who had no intention of going back to Ireland felt a connection to the Fenian movement and were swayed by it. Not to mention, many of the commanders of the Irish ethnic regiments were respected Fenians. These commanders were great motivators for the Irish fighting in the war, since many would follow them simply because of their allegiance to Ireland. This unique Irish quality was yet another reason these brave soldiers from Erin were such fierce fighters.

Nationalism by definition is: loving ones country and wanting to be governed by ones own people. During the second part of the nineteenth century, there was an increased progression of nationalistic feeling in Ireland. Due to this feeling there was a rise in physical force revolutionary groups, the largest organized group being the Fenians. Even though the Fenians started out in Ireland, they also established roots in America, by recruiting large numbers of the new Irish immigrant population. This was easily done due to the fact that the new Irish blamed the English for having to leave their homes in the old country. (1) The Fenian movment was at the height of popularity when the American Civil War broke out. So their ranks decided that fighting in this war would boost the movement as well as being great practice for the eventual uprising in Ireland. Even those who had no intention of going back to Ireland felt a connection to the Fenian movement and were swayed by it. Not to mention, many of the commanders of the Irish ethnic regiments were respected Fenians. These commanders were great motivators for the Irish fighting in the war, since many would follow them simply because of their allegiance to Ireland. This unique Irish quality was yet another reason these brave soldiers from Erin were such fierce fighters.

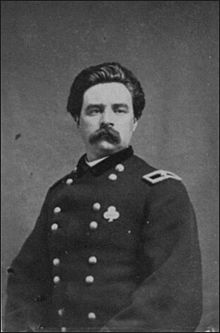

One such commander was John O’Mahony, one of the Fenian movement founders, O’Mahony was born in Ireland in 1816. In 1848 he took part in the failed Ballingarry rebellion and escaped to France. From there he made his way to the United States in 1854. Upon arrival he joined many groups to advance the cause of Irish freedom, one of which was the 69th New York, where he rose to the rank of colonel. During the American Civil War O’Mahony’s rank was mostly political, as he traveled around the nation speaking about the Fenian cause. However, he had a change of heart and felt fighting would help the Fenians cause even more. Therefore, he founded the Phoenix Brigade. At the time the Brigade was founded it was not endorsed as a State of New York military force. However, it was eventually merged into a formal State of New York militia force, designated as the 99th New York State Militia. This made it an Irish Republican military unit subsidized by an independent state. This unit would soon be activated to fight against the Confederate States.

John O’Mahoney (photo right) also planned to use them after the war to invade Canada and strike a blow to the English on foreign soil.

John O’Mahoney (photo right) also planned to use them after the war to invade Canada and strike a blow to the English on foreign soil.

One of the most respected Fenians who inspired the Irish with his ferocious Irish nationalism was Thomas F. Meagher. Meagher succeeded in getting himself into difficulties on both sides of the Atlantic. Born in County Waterford, Ireland and opposed to British rule, he joined the Young Irelanders movement, which was a branch of the Fenians. Meagher quickly rose to a position of power do to his great oratory skills. His most famous speech was the “Sword Speech” given in Dublin on July 28, 1846,

This solidified his power and he was given the moniker “Meagher of the Sword.” Meagher’s prestige in the movement made him an ideal candidate for a diplomatic mission to France, which resulted in him bringing back a flag that would eventually become the Irish Tri-Color, the National flag of Ireland today.

Thomas Francis Meagher (Photo left) like O’Mahony was involved in the failed uprising of the Young Irelanders at Ballingarry, County Tipperary. He was captured, tried, convicted and sentenced to be exiled to Tasmania.

Thomas Francis Meagher (Photo left) like O’Mahony was involved in the failed uprising of the Young Irelanders at Ballingarry, County Tipperary. He was captured, tried, convicted and sentenced to be exiled to Tasmania.

Meagher made a daring escape from his penal colony and landed in America as a hero to the Irish population. He picked up where he left off as an orator for the Irish cause. It was of no surprise that when the American Civil War came about Meagher used his status to raise an Irish Zouave company in 1861 and joined the Union army himself.

He served as the commanding officer of that company and eventually rose to the rank of Brigadier General in the Irish Brigade. Due to his popularity, gained by his actions back in Ireland, his men would fight hard for him. One example of this was at the Battle of Bull Run. The Brigade moved to the right and initially pushed back the enemy. The Confederate forces, with the timely aid of reinforcements, stopped the advancement of the Irish Brigade and began to move the Union forces back. The Irish of the 69th New York would not go down that easily. They rallied and charged multiple times under heavy artillery fire, only to be stopped. During this portion of the battle, General Meagher had his horse shot out from under him. He immediately jumped up, waved his sword, and exclaimed, “Boys! Look at that flag, remember Ireland and Fontenoy”.(a battle during the War of the Austrian Succession in which the Irish Brigade of France achieved victory against an English adversary)

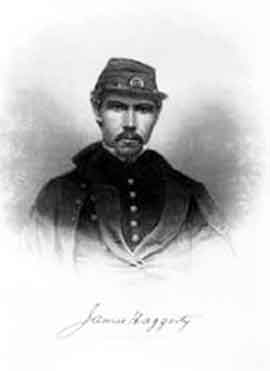

With his nationalist battle cry ringing in their ears, the Brigade made one final push and sustained substantial casualties. One of these casualties was  Lieutenant Colonel James Haggerty, a native of Co. Donegal Ireland, who was styled by Tipperary born Captain David Power Conyngham “as fine a specimen of a Celt as Ireland could produce.”

Lieutenant Colonel James Haggerty, a native of Co. Donegal Ireland, who was styled by Tipperary born Captain David Power Conyngham “as fine a specimen of a Celt as Ireland could produce.”

James Haggerty was just one of many men who perished valiantly that day. After the battle the Commander of the Union Army, General Irving McDowell, who watched the charge, rode up to the 69th and personally thanked them. Meagher lead the Irish Brigade in every battle up till and including the Battle of Fredericksburg. The 69th succeeded in joining with the main attack, and many more of the regiment would die as they unsuccessfully charged the Confederate positions on Henry Hill. The day ended in defeat for the Union, and the war would continue for four bloody years. We can only speculate as to why James Haggerty so exposed himself in an effort to capture the fleeing Rebels. Perhaps he felt confident they were routing, or suffered a rush of blood to the head in what was his first battle. Maybe as he had shown in the past he was eager to set an example for his men.

James Haggerty was the first man of the 69th New York State Militia to die in the Battle of Bull Run. His experience of combat lasted a matter of minutes before he was killed, leaving behind a widow and infant daughter. Later in the year Thomas Francis Meagher, Captain of Company K (Meagher’s Zouaves) of the 69th and future commander of the Irish Brigade, said that of all the regiment’s dead at Bull Run, Haggerty was ‘Prominent amongst them, strikingly noticeable by reason of his large, iron frame, and the boldly chiseled features, on which the impress of great strength of will and intellect was softened by a constant play of humor and the goodness and grand simplicity of his heart- wrapped in his rough old overcoat, with his sword crossed upon his breast, his brow boldly uplifted as though he were still in command, and the consciousness of having done his duty sternly to the last still animating the Roman face -there lies James Haggerty- a braver soldier than whom the land of Sarsfield and Shields has not produced, and whose name, worked in gold upon the colors of the Sixty-ninth, should be henceforth guarded with all the jealousy and pride which inspires a regiment, wherever its honor is at stake and its standards are in peril.

Although Meagher’s military service with the Irish Brigade did not last the duration of the war, his leadership and inspiration magnificently guided the Brigade through many of its hardest battles.

Another Irish Nationalist who had a positive effect on the fighting spirit of the Irish in the American Civil War was Michael Corcoran. Corcoran was born in Carrowkeel, county Sligo Ireland and was a member of the Irish Nationalist Guerrilla force known as the Ribbonman. His ties to this group were eventually discovered in 1849 so he immigrated to New York City in order to avoid capture.

To gain a position in society he joined the 69th New York State Militia as a private. This would not last as “his military passion and his previous knowledge of military tactics were a great advantage to him.”

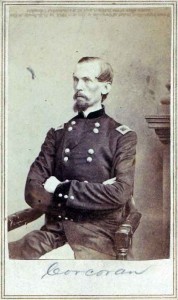

Michael Corcoran (Photo Left) moved up in rank and became a Colonel. It was in this capacity that Corcoran became a hero to the Irish Nationalist, as well as the overall Irish immigrant population of New York. He chose not to parade his men in front of the Prince of Wales upon his visit, saying that “as an Irishman he could not consistently parade Irish-born citizens in honor of the son of a sovereign, under whose rule Ireland was left a desert and her best sons exiled or banished.”

Michael Corcoran (Photo Left) moved up in rank and became a Colonel. It was in this capacity that Corcoran became a hero to the Irish Nationalist, as well as the overall Irish immigrant population of New York. He chose not to parade his men in front of the Prince of Wales upon his visit, saying that “as an Irishman he could not consistently parade Irish-born citizens in honor of the son of a sovereign, under whose rule Ireland was left a desert and her best sons exiled or banished.”

His action resulted in a court-martial. However, it was overturned due to the need of good officers to fight in the Civil War. Corcoran resumed his rank in the 69th New York and was present at that Battle of First Manassas, where he was captured. Corcoran spoke of this later by saying, “I did not surrender until I found myself after having successfully taken my regiment off the field, left with only seven men and surrounded by the enemy.”

Corcoran was eventually exchanged over a year later, and was received back with acclaim. He was given the rank of Brigadier General and put in command of his own troops, known as Corcoran’s “Irish Legion.” The first battle of the Legion took place during the Battle of Deserted House Virginia. Although not one of the biggest battles of the war, Corcoran demonstrated calmness under fire and his men showed how they admired Corcoran by following his every commanded under intense battle conditions.

Sadly this would be Corcoran’s last major battle as he was killed later that year when he fell from his horse. Even though Corcoran’s life was cut short his legend and the Prince of Wales incident continued to inspire men, especially those of his Legion who were fighting for Uncle Sam as well as Irish pride.

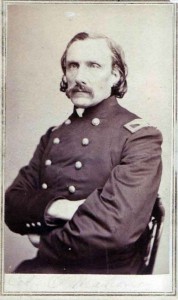

Thomas Alfred Smyth (December 25, 1832 – April 9, 1865 Photo Right) was a brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was the last Union general killed in the war. In March 1867, he was nominated and confirmed a brevet major general of volunteers posthumously to rank from April 7, 1865.

Thomas Alfred Smyth (December 25, 1832 – April 9, 1865 Photo Right) was a brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was the last Union general killed in the war. In March 1867, he was nominated and confirmed a brevet major general of volunteers posthumously to rank from April 7, 1865.

Smyth was born in Ballyhooly in Cork County, Ireland, and worked on his father’s farm as a youth. He emigrated to the United States in 1854, settling in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He participated in William Walker’s expedition to Nicaragua. Smyth was employed as a wood carver and coach & carriage maker. In 1858, he moved to Wilmington, Delaware.

Between July 31, 1864 and August 22, 1864 and between December 23, 1864 and February 25, 1865, Smyth commanded the 2nd division of the corps. In April 1865 near Farmville, Virginia, Smyth was shot through the mouth by a sniper, with the bullet shattering his cervical vertebra and paralyzing him. Smyth died two days later at Burke’s Tavern, concurrent with the surrender of Robert E. Lee and his army at Appomattox Court House.

On March 18, 1867, President of the United States Andrew Johnson nominated Smyth for posthumous appointment to the grade of brevet major general of volunteers to rank from April 7, 1865, the date he was mortally wounded, and the United States Senate confirmed the appointment on March 26, 1867. Smyth was the last Union general killed or mortally wounded during the war, and is buried in Brandywine Cemetery in Wilmington, Delaware.

The Union was not the only beneficiary of Irish Nationalist leadership due to the fact that many of the Irish in the south felt the situation in America mirrored the situation in Ireland with Great Britain. They felt an aggressive big government had taken on the smaller independent state, and that was something they could support fighting against, one such leader was Patrick Ronayne Cleburne. Cleburne was born in the late 1820s to a middle class Irish Protestant family in County Cork, Ireland. He had an ambition to be an apothecary but he failed the entrance exam for the medical school. So for economic reasons he joined the British army even though he believed it to be “a symbol for tyranny.”

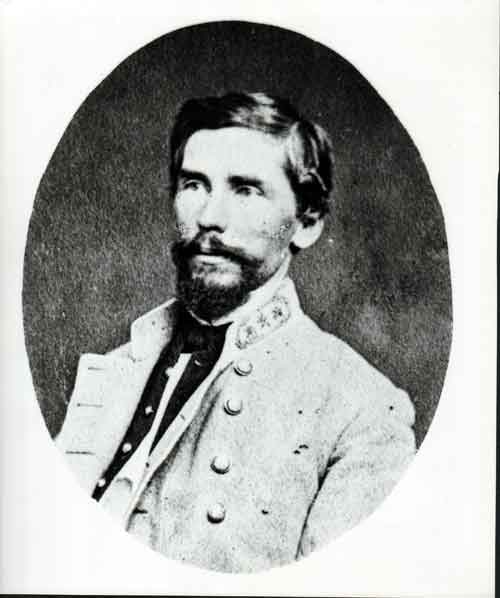

Patrick Cleburne’s (Photo Left) time in the army was served in a unit that preformed civil duties in famine stricken Ireland. By 1849 the famine finally caught up to him and his family, so he and his sister immigrated to America.

Patrick Cleburne’s (Photo Left) time in the army was served in a unit that preformed civil duties in famine stricken Ireland. By 1849 the famine finally caught up to him and his family, so he and his sister immigrated to America.

Cleburne eventually settled in Arkansas where he joined many social clubs, including a Militia Company called the Yell Rifles, and was soon elected captain.

When the American Civil War broke out Cleburne was in charge of the Yell’s and marched them off to war. Soon his military prowess was noticed by Confederate commander William J. Hardee and he was promoted to Brigade Commander.

Cleburne served with distinction, most notably his stand at Ringgold Gap where his 4,000 men held off the superior numbers of General Hooker’s Union troops.

During the battle, Cleburne personally took command of his battery units and waited for the Federal forces to get within a short distance. He kept his men calm till the enemy was in the precise position for their guns to inflict the most damage. Cleburne then shouted, “NOW!! Lieutenant, give it to em!”

The canister shot devastated the Union line and drove them back. For this act Commander Cleburne received a Congressional Citation from the Confederate Congress, and earned the nickname “Stonewall of the west.”

In November of 1864 Cleburne met his fate during the battle of Franklin, Tennessee. During the battle Cleburne had two horses shot out from under him then continued on foot drew his sword and charged head strong toward the Federal lines. As he urged his men forward and got within paces of the Union breastworks he was shot through the heart.

Cleburne died a hero’s death for his adopted land. However, after reading his words one can easily make the assumption that in his mind he gave his last full measure for Ireland as well. This can be seen in Cleburne’s Proposal to Arm Slaves. In this letter to Confederate commanders he writes, “As between the loss of independence and the loss of slavery, we assume that every patriot will freely give up the latter — give up the negro slave rather than be a slave himself. If we are correct in this assumption it only remains to show how this great national sacrifice is, in all human probabilities, to change the current of success and sweep the invader from our country.”

From this quote one can easily infer that Cleburne saw the parallels between the South’s struggle in the American Civil War and Irelands fight against English oppression. He was like other southern Irishmen inspiring to join the war effort with a fervent passion to vanquish their northern aggressors.

The Irishmen who felt the similarities between the south and Irish Nationalist fought with great vigor against the Federals, and stated their desire to subjugate their oppressive foe, when they chose the names for their regiments. A unit in the 1st Missouri Brigade evoked the name of the bold Robert Emmet, and Irish rebel and patriot, when they chose to be called Emmet Guards.

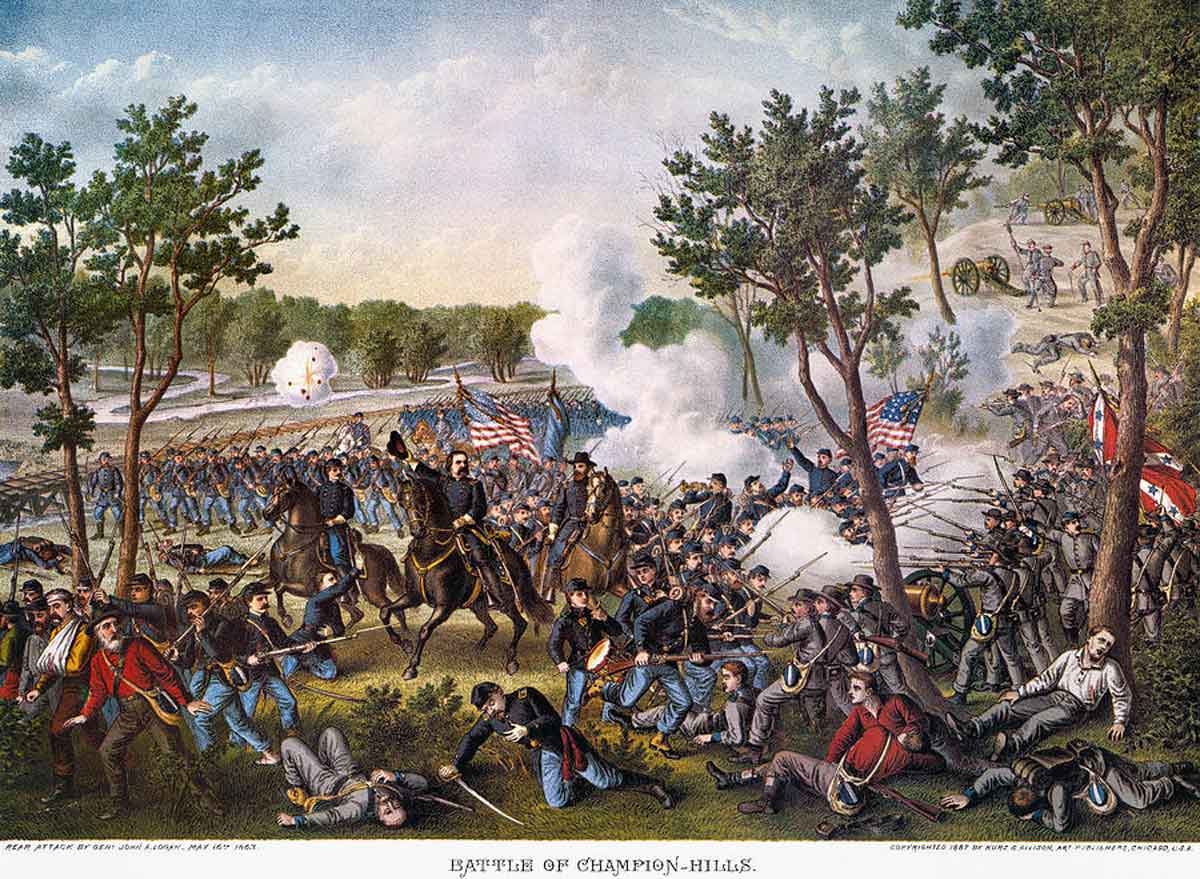

The Emmet Guards distinguished themselves at the Battle of Champion Hill, Mississippi. The action of the battle was described as such, “With flags flying and the rebel yell erupting from their mouths. The Missouri Confederates advanced, driving the bluecoats back, recapturing lost batteries, and gaining much ground. Bitter hand to hand fighting swirled over the rough terrain, among the magnolias, deep gullies, and dense woodlands of Champion Hill.”

The Emmet Guards distinguished themselves at the Battle of Champion Hill, Mississippi. The action of the battle was described as such, “With flags flying and the rebel yell erupting from their mouths. The Missouri Confederates advanced, driving the bluecoats back, recapturing lost batteries, and gaining much ground. Bitter hand to hand fighting swirled over the rough terrain, among the magnolias, deep gullies, and dense woodlands of Champion Hill.”

The Irish from Missouri almost split the Union line in two before Federal reinforcements arrived and drove the rebels back. The Irishmen of the Emmet Guards did their namesake proud but suffered heavily for their effort.

Battle of Champion Hill By Kurz & Allison published in 1887

Battle of Champion Hill By Kurz & Allison published in 1887

Another southern battalion born out of Irish Nationalism was part of the 1st Virginia and named the Montgomery Guards, after the Irish born American Revolutionary war hero General Richard Montgomery.

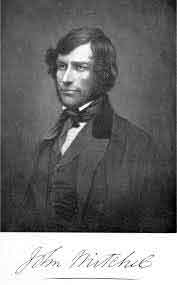

Additionally, this unit has another strong tie to Irish patriotism and national pride. William Henry Mitchel, the son of John Mitchel Senior, an exiled Irish revolutionary and leader of the Young Irelander movement, served in its ranks. John C. Mitchel instilled the ideas of Irish nationalism into his son and explained how Irelands struggle was almost identical to that of the south.

Young William took those ideas into battle with him at Gettysburg. William was elected to be the color barer of the 1st Virginia and led them into what would be forever remembered as Pickett’s Charge. He was severely wounded and about to be escorted to the rear but refused in order to advance the standard of his regiment with a sense of Irish pride. ‘We are sorry to learn that Wm. Mitchel, youngest son of John Mitchell, Esq., editor of the Enquirer, who was reported missing after the battle of Gettysburg, is now believed to have been killed in that hard-fought struggle. Young Mitchel was only eighteen years old, and is represented to have been a young gentleman of fine attainments, and an excellent soldier, and behaved with especial gallantry at Gattysburg. He has two brothers in the Confederate Service.’

Young William took those ideas into battle with him at Gettysburg. William was elected to be the color barer of the 1st Virginia and led them into what would be forever remembered as Pickett’s Charge. He was severely wounded and about to be escorted to the rear but refused in order to advance the standard of his regiment with a sense of Irish pride. ‘We are sorry to learn that Wm. Mitchel, youngest son of John Mitchell, Esq., editor of the Enquirer, who was reported missing after the battle of Gettysburg, is now believed to have been killed in that hard-fought struggle. Young Mitchel was only eighteen years old, and is represented to have been a young gentleman of fine attainments, and an excellent soldier, and behaved with especial gallantry at Gattysburg. He has two brothers in the Confederate Service.’

The New York Irish-American, despite being a pro-Union northern newspaper, joined in the mourning for the Irish nationalist’s son, despite the fact that he had been a Confederate. On the 12th September they wrote the following eulogy:

JOHN MITCHEL’S YOUNGEST SON

‘We have received with sincere sorrow the intelligence that William Mitchel, the youngest of John Mitchel’s sons, fell mortally wounded on the battle-field of Gettysburgh, shot through the lower part of the abdomen. He was in the color-guard of the 1st Virginia regiment, and fell near the breastworks held by the 3d corps, in the last desperate charge which Longstreet’s troops made upon the position. He was a young lad of the highest promise, and never failed to endear himself to those with whom he was brought in contact, by the sterling goodness of his disposition and the many excellent traits of character he displayed. Few who remember the bright, open-hearted boy, who, three short years ago, was the life of a yet unbroken family circle in the vicinity of this city, but will join in the regret with which we now record his untimely fall upon a field where brother strove with brother in deadly conflict that could bring naught of good to either. Mr. Mitchel’s family have been sorely afflicted within a few short months. It is but the other day we had to chronicle the death of his eldest daughter in Paris; and now another of his children has gone to his last rest, far from home, and from the friends whose ministrations, at least, might have made lighter the steps that lead to the grave.’

The Irishmen of the 1st Virginia fought that day “not only with pride in the centuries long Irish revolutionary heritage and the legacy of their Irish rebel forefathers but also in the rich traditions of their regiment as well.”

The use of Irish Nationalism proved to be successful motivation for Celtic men on both sides of the American Civil War. It was a source of enthusiasm that other regiments in the conflict did not have. Therefore, one can say this was a uniquely Irish trait, and one that would have made them more powerful on the battlefield.

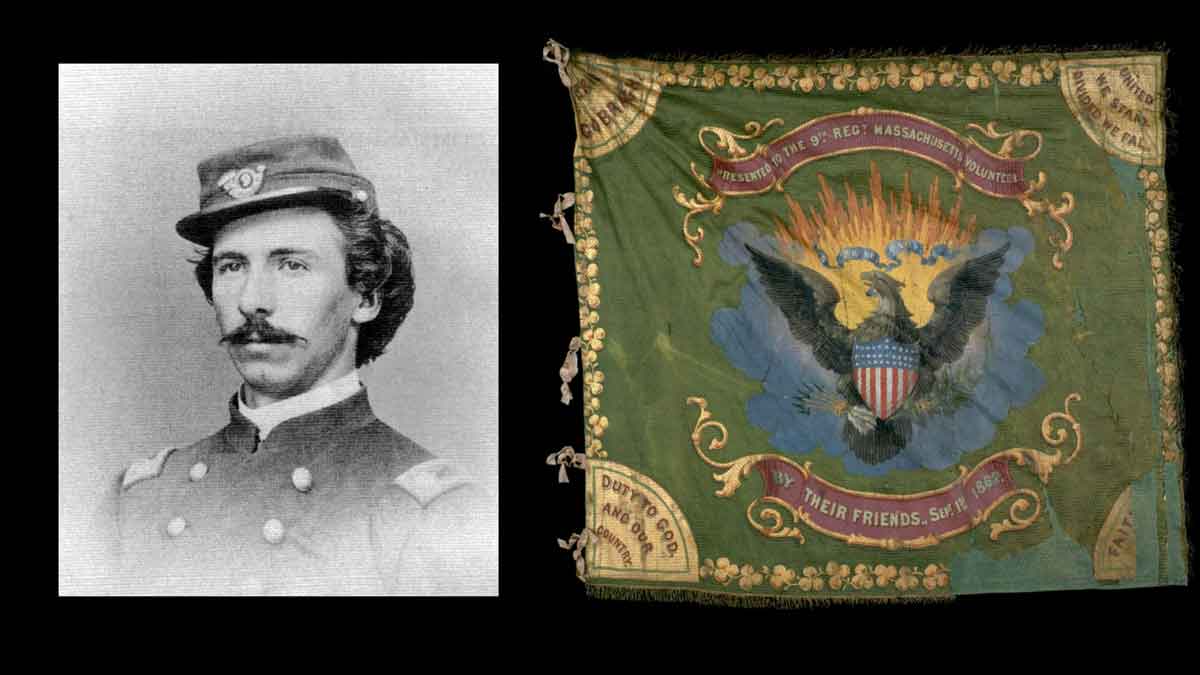

Left: Colonel Patrick Robert Guiney Right: The Colors Of The 9th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

Left: Colonel Patrick Robert Guiney Right: The Colors Of The 9th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

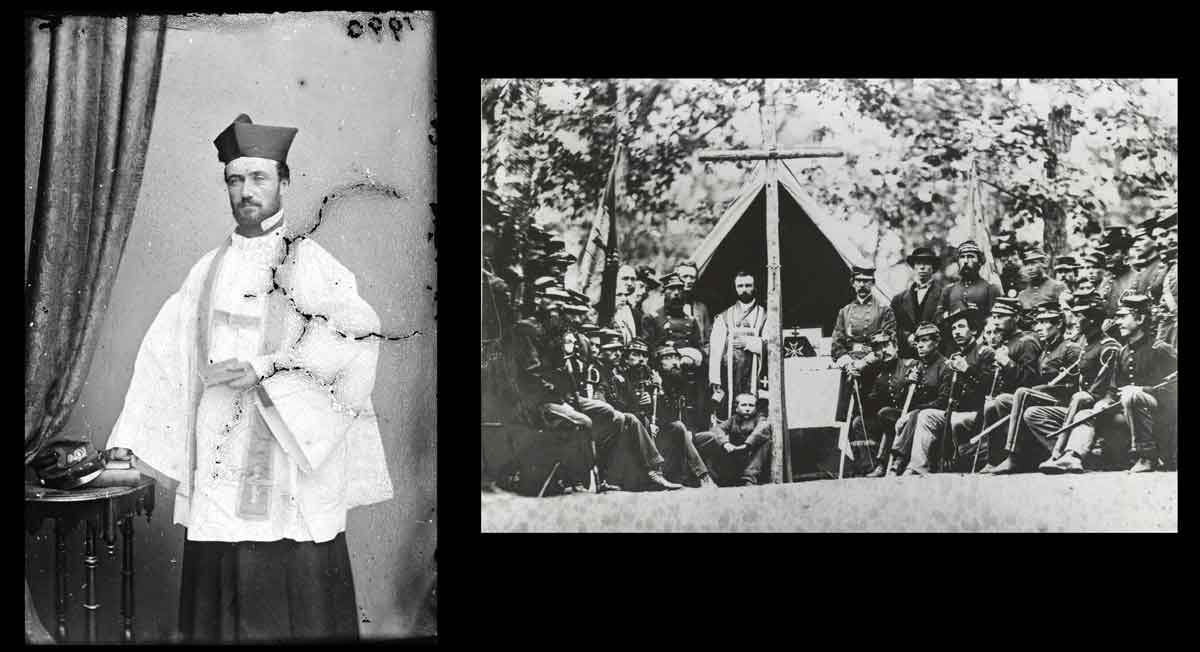

Left: Father Thomas Scully Right: Father Scully prepares to say mass to Bostons Irish 9th at Camp Cass, Arlington Heights, Virginia.

Left: Father Thomas Scully Right: Father Scully prepares to say mass to Bostons Irish 9th at Camp Cass, Arlington Heights, Virginia.